Tokorozawa Aviation Museum

To the average Japanese on the street, the mention of Saitama conjures up images of “bed cities” for Tokyo’s commuters, it being one of the cluster of prefectures around the capital that are bucking the demographic trend of population decline. At the propeller turn of the 20th century, however, this then rural area witnessed epoch-making events that led to what was then the village (since 1950, city) of Tokorozawa becoming known as the birthplace and as a once hotbed of Japanese aviation.

In general, this dedicated page follows the format begun with the Gifu-Kakamigahara Air and Space Museum coverage. One noticeable difference in this case, in the absence of detailed English-language information on site, is the inclusion of translations of selected display panels. Please note that, once again, topics not covered by this website, such as space exploration, are not included.

See the October 2023 Bulletion Board report for an update to this page.

Note: The H-19C and V-44A helicopters are due to be removed when TAM undergoes a major tenovation, which is slated to commence some time in 2025.

Contents

Place in History Cemented on Grass

Getting the Lie of the Land

Museum Beginnings

Perennial Gate Guard

Entrance Lobby

Main Exhibition Hall

Ground Floor Exhibits

Exhibits Hanging in Suspended Animation

Adjoining Exhibition Rooms

Upper Level Exhibits/Panel Displays

Tokorozawa Memorial Gallery (The History of Tokorozawa)

Military Aviation Treasure House: Aviation Reference Hall

Display of Collected Documents

Zone names, as they appear:

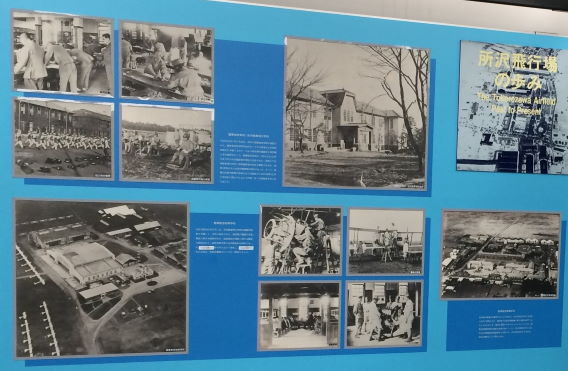

(1) The Tokorozawa Airfield Past to Present [Part 1]

(2) The Beginning of the Aviation Era

(3) Japan’s First Airfield

(4) The Tokorozawa Airfield Past to Present [Part 2]

(5) The Tokorozawa Airfield Following World War II

(6) The Tokorozawa Airfield Molding Japan’s Aviation History

(7) Saitama Prefecture and Tokorozawa Airmen

Airplanes over Tokorozawa

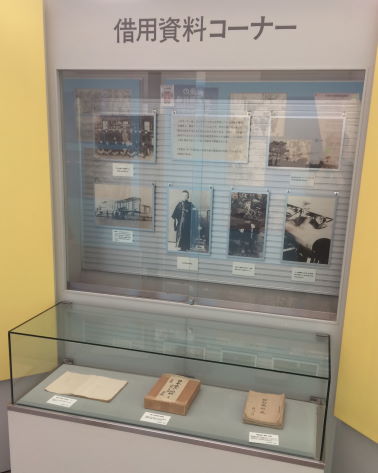

Section for Materials on Loan

Achievements of Aeronautical Designers

(See October 2023 Bulletin Board story for brief update)

Storage Hangar

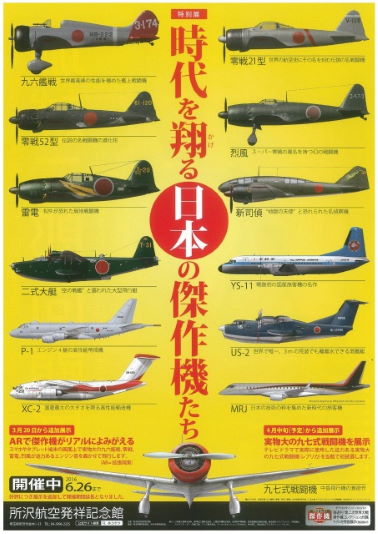

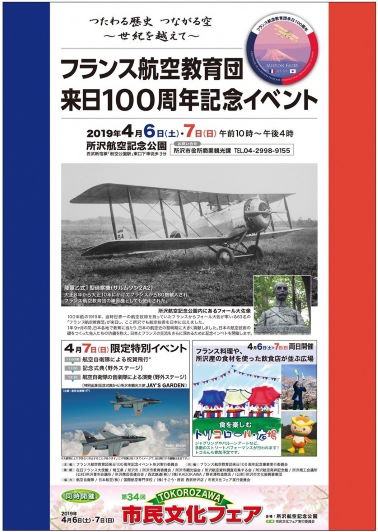

Special Events/Temporary Exhibits

Monuments Located in Aviation Park

Future Prospect Flights of Fancy

Going Back in Time: Tokorozawa Aviation Museum, October 2000

Checklist Complete

Museum Information/Getting There and Back from Tokyo

A general view of the Tokorozawa Aviation Museum’s main exhibition hall in November 2019. Although

A general view of the Tokorozawa Aviation Museum’s main exhibition hall in November 2019. Although

the large helicopters and dangling exhibits have not surprisingly remained where they were placed for

the opening in 1993, changes are made to the layout when needed to accommodate a

temporary exhibition or commemorate a special event.

Place in History Cemented on Grass

After selection by the Imperial Japanese Army as the site of its first airfield, Tokorozawa became operational on April 1, 1911. On the morning of April 5, Capt. Yoshitoshi Tokugawa, piloting a Farman HF7, became the first Japanese to fly, albeit briefly, from a dedicated military air base. From these modest beginnings, Tokorozawa became the centre for both pilot training and the nascent Japanese aviation industry. (You can find out more about Capt. Tokugawa in the first story on the Japanese Aviation History page of this website.)

Getting the Lie of the Land

Japan established a Provisional Military Balloon Study Group* in July 1909, more than five and a half years after the Wright Brothers had hit the headlines following their flight of December 17, 1903. The aim in forming an organization to study aviation technologies, even one that was already sporting an anachronistic name, was to catch up with developments unfolding in the West. It was under the auspices of the study group that Capts Yoshitoshi Tokugawa and Kumazō Hino were sent to France and Germany, respectively, to learn to fly and to bring back the aircraft in which they would themselves enter the history books in December 1910. (Again, see first story on the Aviation History page of this website.)

In the meantime, one of the first projects with which the study group was tasked was the selection of a suitable location for Japan’s first military airfield. Aside from Tokorozawa, the candidate sites were Otawara and Utsunomiya (both in Tochigi Prefecture), Odawara (Kanagawa) and Shimoshizuhara (Chiba). Saitama Prefecture beat off its rivals because of Tokorozawa’s good rail connections with Nakano in Tokyo, where the study group was based, and its topography and climate were suitable for balloon (or rather, as things turned out, small airship) operations.

On April 1, 1911, the study group’s Tokorozawa test facility was established on the site of the first airfield in the country, which featured a runway 50 metres wide and 400 metres long and a weather station. Initially, only four aircraft were operated, a Henri Farman, Hans Grade, Blériot and a Wright Flyer.

The first practice flights from Tokorozawa airfield took place between April 5 and 15 of that same year. In the early morning of the first practice, Tokugawa piloted a Henri Farman in completing the first flight from Japan’s first airfield, reaching an altitude of all of 10 metres and covering 800 metres in a flight time of 1 minute 20 seconds.

A number of other “firsts” were achieved, including the building of the first indigenously produced airship, the Kaishiki I-Gō (kai-shiki being a combination of the words for ‘group’, from Provisional Military Balloon Study Group, and ‘type’), and the first domestically produced military aircraft in Japan, the Kaishiki Ichi-Gō. Based on a Henri Farman design, the latter flew for the first time on October 13, 1911, again with that man Tokugawa at the controls. Alongside its responsibilities for the production of early aircraft and airships, the Tokorozawa facility assumed responsibility for pilot training.

Japan’s first domestically produced military aircraft, the 1911-vintage Kaishiki Ichi-Gō, at Tokorozawa.

Japan’s first domestically produced military aircraft, the 1911-vintage Kaishiki Ichi-Gō, at Tokorozawa.

This is the same image that appears on the photo display in the entrance hall.

(Photo: via Wikimedia Commons)

In many ways a victim of its own success, space was already at a premium and inadequate for testing then state-of-the-art, high-performance aircraft as early as 1918. When the French Military Aviation Mission arrived in Japan in the following year, Tokorozawa was the venue for aircraft construction and airship activities.

To concentrate on its role as an Army flying school, Tokorozawa’s then new aircraft research and design department was moved to Tachikawa in 1928. More information on this period follows in the section that deals with and provides a guide to selected display panels and exhibits.

* Although there are many possible variations for the English name of the Rinji Gunyō Kikyū Kenkyūkai, such as Provisional Society for Military Balloon Research, this is the preferred translation that appeared in the book They Flew Regardless (Japan Aeronautic Association, 2013).

Museum Beginnings

Even long after the end of the postwar Allied Occupation of Japan, U.S. forces continued to utilize Tokorozawa as a supply base before vociferous calls for its return to Japanese ownership began to be answered; around 70% of the base area had already been returned by 1982.

The local authorities then hit upon the plan to mark the area’s aviation links by opening Japan’s first specialist aviation museum where an ex-JASDF EC-46D had been placed in 1980, the site of the former airfield now being a Saitama Prefecture-managed public park. Research into and the collection of aviation artefacts and materials continued alongside the construction of the museum building, which was commenced in November 1990. To bolster the number of exhibits, the JGSDF collection formerly housed at Kisarazu AB was brought under one roof in the purpose-built facility, which was opened on April 3, 1993. Although not located adjacent to an active base, Tokorozawa essentially became the central repository for former JGSDF aircraft types, the service’s answer to the JASDF and JMSDF collections at Hamamatsu and Kanoya, respectively.

The C-46 is just visible in the centre of this aerial view of Kōkūkōen (Aviation Park) taken in 1989, four

The C-46 is just visible in the centre of this aerial view of Kōkūkōen (Aviation Park) taken in 1989, four

years before the addition of an aviation museum. On the left, Kōkūkōen Station on the Seibu Shinjuku

Line was opened in May 1987. (Photo: National Land Image Information (Color Aerial Photographs),

created by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism and distributed by the

Geospatial Information Authority of Japan, via Wikimedia Commons)

Now under the private management of the Tokyo-based Japan Science Foundation (JSF) and officially known as the Kōkūhasshōkinenkan—literally the Origins of Aviation Memorial Museum—the facility has become a mecca for anyone with an interest in aviation. More simply marketed as the Tokorozawa Aviation Museum (TAM), its setting in the pleasant expanse of the Kōkūkōen (Aviation Park), with ample parking and close to a train station that shares the same short name, guarantees more than a passing trade from visitors.

Comparative visitor figures appeared in a document produced by the then Kakamigahara Air and Space Museum when plans were being made for its expansion. In 2013, the TAM attracted 354,000 visitors, compared with 123,000 at Kakamigahara and only 110,000 at the Misawa Aviation and Science Museum. Boosted by the long-term presence of a unique Zero fighter (see later), which accounted for record-breaking visitor numbers, the TAM figure was hardly representative.

According to the Japan Science Foundation’s Business Report for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2018 (FY2017), the total of 181,979 visitors comprised 22,331 in 390 groups (a group being 20 or more people) and 159,648 individuals. However, this represented a decrease of 25,127 visitors compared with the previous year. In fiscal 2018, ended March 31, 2019, the total number of visitors increased 6.9%, to 194,567.

| Tokorozawa Aviation Museum Visitor Numbers | |||||||

| FY2012 | 375,332 | FY2014 | 195,831 | FY2016 | 207,106 | FY2018 | 194,567 |

| FY2013 | 353,869 | FY2015 | 184,769 | FY2017 | 181,979 | FY2019 | 175,883* |

* Closed March 2 to end of fiscal year on March 31, 2020, due to COVID-19

At the end of March 2003, 10 years after opening, the cumulative total of visitors had reached at 2,655,249. The figure passed the six million milestone on July 2, 2016, and 6.5 million on February 16, 2019.

The airship hangar-like main building of the Tokorozawa Aviation Museum in April 2017.

The airship hangar-like main building of the Tokorozawa Aviation Museum in April 2017.

The storage hangar is on the extreme right.

Perennial Gate Guard

(Photo: May 2013)

(Photo: May 2013)

Unmissable to visitors as they make their way around to the museum entrance, the first aircraft encountered is an ex-JASDF EC-46D (above) in a fenced-off enclosure. Handed over to the service as a standard C-46 for training purposes on December 22, 1959, the aircraft was upgraded to C-46D transport configuration and later to EC-46D ECM trainer standard before being withdrawn from active service at Iruma on April 19, 1978. Although placed in the park in March 1980, the earliest photo that J-HangarSpace has managed to find of the aircraft in its current location was taken in April 1989, four years before the museum opened.

Mentioning the name Tenma (Pegasus), which was that bestowed on this type of aircraft in January 1964, the sign next to the enclosure giving information on the C-46 Medium Transport Aircraft reads:

In total, 3,180 C-46 transports were built by the U.S. Curtiss-Wright Corporation from March 1940.

First used as military transport aircraft, many were operated after the war as civil transports.

In Japan, the C-46D was first supplied as the JASDF’s transport aircraft in January 1955, and the last C-46A of a total of 47 more of the type taken on strength in December 1959. Referred to as the “D51 of the Skies” [a reference to the D51 Class steam locomotive manufactured in Japan from 1936 to the end of the war], the C-46 provided sterling service in a wide variety of roles with the JASDF, including the airlift of relief supplies in the aftermath of natural disasters.

The C-46A transport [actually EC-46D] displayed here in Tokorozawa Aviation Memorial Park was operated from JASDF Iruma AB. In March 1980, the aircraft was disassembled for transportation to the park, where it was placed to serve as its symbol.

The aircraft’s dimensions are: wingspan 32.9m; length 23.3m; and height 6.6.m; its weight is 13.6 tons. The 2,000hp, 18-cylinder, air-cooled engines were made by Pratt & Whitney [R-2800 Double Wasp engines]. The aircraft’s maximum speed was 433km/h, its ceiling 8,400m and its operational range 2,200km. The aircraft had a crew of five and could carry 50 people.

[The sign is dated March 2011.]

Placed next to the rock memorial close to the C-46 enclosure (seen in the above photo), another sign provides some of the back story. A translation of the information is provided below.

(Photo: May 2013)

(Photo: May 2013)

|

City of Tokorozawa Designated Cultural Property (Historic Site) Birthplace of Japanese Aviation |

||

| The City of Tokorozawa is said to be the birthplace of Japanese aviation as Japan’s first airfield was established here in April 1911. In July 1909, the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group was formed by Imperial edict and Upon its establishment, Tokorozawa airfield covered an area of roughly 76 hectares [190 acres]. Managed by Saitama Prefecture, this Tokorozawa Aviation Memorial Park is a municipal facility built The first flights from Tokorozawa airfield commenced early in the morning of April 5, 1911. First to It is said that, in addition to Tokorozawa residents, many visitors gathered from nearby places to see |

||

| City of Tokorozawa Board of Education, March 2011 | ||

Its inscription reading Birthplace of [Japanese] Aviation, this memorial was dedicated on April 5, 2000,

Its inscription reading Birthplace of [Japanese] Aviation, this memorial was dedicated on April 5, 2000,

to mark the 50th anniversary of Tokorozawa being granted city status. (Photo: May 2013)

Looking older than its years, the plaque on the back of the rock pictured above reads:

Japan’s first airfield was established on this site in 1911. Early in the morning of April 5 that same year, a Henri Farman aircraft piloted by Capt. Tokugawa successfully completed the first flight [from here]. Having from that time contributed to the development of the aviation industry in this country, Tokorozawa has been known as the “birthplace of aviation.”

City of Tokorozawa

Society for Investigating and Gathering Tokorozawa Aviation Materials

April 5, 2000

Located close to the C-46, this sign has been positioned half way along where the runway was in 1911 to

Located close to the C-46, this sign has been positioned half way along where the runway was in 1911 to

show the position of today’s park in relation to the Army airfield. If you look up from the sign (below),

you can use your imagination to add the details from the photos on the sign. The weather observatory

(second photo from top) would have been straight ahead, the hangar (third photo) would have

been to your left, obstructing your view of the airfield’s main gate beyond.

(Photos: [above] May 2013); [below] Feb. 2020)

The entrance to Tokorozawa Aviation Museum at the time of a special Zero exhibit in May 2013.

The entrance to Tokorozawa Aviation Museum at the time of a special Zero exhibit in May 2013.

The hiragana topiary in front of the museum, the first two bushes of which can be

seen here, spells out こうくうこうえん (Kōkūkōen [Aviation Park]).

Entrance Lobby

(Photo: February 2020)

(Photo: February 2020)

Flanked by a café-restaurant featuring a terrace and the Flying Spirits souvenir shop, the entrance lobby naturally provides orientation information for visitors. The aircraft suspended from the ceiling (pictured above), which forms the focal point of the lobby area, is a replica of the Kaishiki Ichi-Gō that Yoshitoshi Tokugawa flew for the first time from Tokorozawa on October 13, 1911. Although heralded as the first aircraft made in Japan, it was strictly speaking merely a modified Farman.

(Photo: February 2020)

(Photo: February 2020)

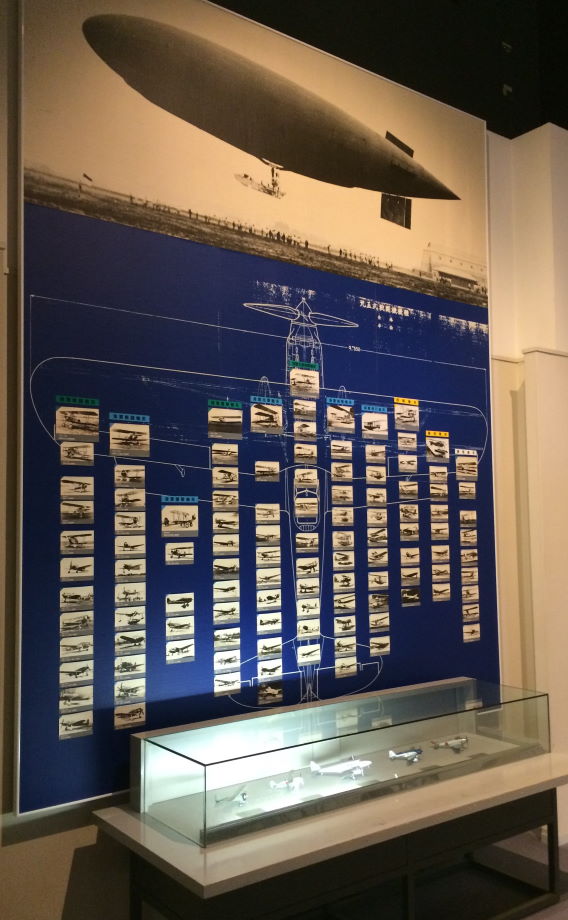

Entitled Airplanes which Shaped Japanese Aviation History, the display panel (above) positioned beneath the replica provides photos and information of the aircraft that feature in the history display on the upper level. Of note is the Wright aircraft (on the bottom right of the panel), which is given as being from Germany, as the example that Army Capt. Kumazō Hino arranged to have imported was built there rather than in the United States.

Directly accessible on the ground floor (1F in Japan) from here is a 200-seat cinema that mainly caters for the younger visitor.

Main Exhibition Hall

Its entrance located right next to the ticket counter, the main exhibition hall features several aircraft suspended from the ceiling over a “runway”, while adjoining areas provide themed displays in hangar and workshop (1F) and control tower (2F) settings. (The real-life Tokyo area air traffic control centre happens to be located across the street from the car park.)

The museum emphasizes its educational role by means of the workshop, a research/study room, where young visitors in particular can learn about the principles of flight, and a “factory” where they can gain hands-on experience of “flying” a Cessna T310P. Naturally, aircraft (two-axis) and helicopter simulators have also been installed, on the 2F level. Deservedly trumpeting Japan’s recent successes, all the space-related exhibits have been grouped together on the 1F level.

The area along the windows is utilized for temporary panel displays, and exhibits at the far end are subject to change and often tied in to special exhibits. In recent years, these have included the visit of an airworthy Zero, the replica of a Nakajima Ki-27 (Nate) fighter used in a TV drama, and a Henri Farman, photos from which are included later on this page.

Although not all are on permanent display, the collection includes a number of JGSDF helicopter types, which span the years from the service’s formation on July 1, 1954, to 2002, when the last KV-107II was retired.

(1) Ground Floor Exhibits (relevant to J-HangarSpace content, in order they appear to visitors entering from lobby)

The blue numbers are those in the Runway and Apron section of the free audio guide, which provides short, general commentaries in adequate English and fast French (as well as Japanese and soon Korean) via your smartphone, so have your earphones handy. To access the audio guide you just need to scan the QR code provided on a sign. Aside from the many spelling errors and inaccuracies on the navigation screens, be warned that the English guide sounds very amateurish, and the narration is by a woman whose first language seems to be French! On the positive side, she does a perfect job with any French (and German) names.

(Photo: April 2017)

(Photo: April 2017)

(1) North American T-6G Texan (52-0099, exhibited since April 1993 opening)

Delivered to the JASDF on September 23, 1955, the former U.S. Air Force T-6G 51-15058 was passed to the Tokyo Metropolitan College of Industrial Technology in October 1965, five months after its retirement from active service, on May 1 of that year.

(Photo: November 2019)

(Photo: November 2019)

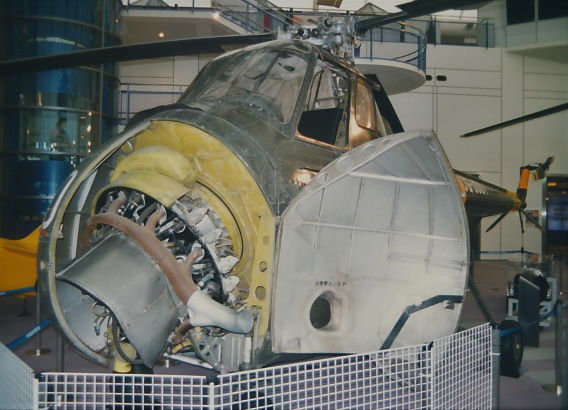

(2) Sikorsky H-19C (40001, exhibited since April 1993 opening)

The JGSDF operated a total of 31 H-19Cs, the first five of which were S-55s and the remainder S-55Cs (Mitsubishi-built from the 18th aircraft). The first two S-55s were actually delivered in June 1954, a matter of days before the JGSDF came into being, that July 1. The example on display was the second delivered, on June 16, 1954, and served until February 12, 1973, the year in which the last three S-55s were retired. (The remaining S-55C variants soldiered on for another three years.) Last operated by the Aviation School’s Kasumigaura branch, the aircraft was placed in storage at Kisarazu.

(Photo: November 2019)

(Photo: November 2019)

(6) Vertol V-44A (50002, exhibited since April 1993 opening)

The second of two Vertol V-44A (H-21C) transport helicopters, which were on active service from 1959 to 1969, forms the centrepiece. Delivered on July 21, 1959, this aircraft had been withdrawn from use and placed in storage at Kisarazu on February 20, 1970.

(Subsequent information: In October 2021, the TAM deputy director confirmed to J-HangarSpace that, at a date yet to be decided, the H-19 and V-44A were to be returned to the SDF.)

(Photo: November 2019)

(Photo: November 2019)

Fuji T-1B (25-5856, first exhibited March 19, 2006, present again in November 2019 after period spent in storage hangar)

The sixth T-1B and thus the 52nd of the 66 T-1s built, this aircraft was delivered to the JASDF’s 13th Flying Training Wing on December 13, 1962. Repaired after having been involved in an accident on June 8, 1992, the aircraft was retired from service when being used for air traffic controller training with the 5th Technical School at Komaki on July 16, 2005. Dismantled into 10 main assemblies at the 1st Technical School at Hamamatsu, ’856 was re-assembled over a four-day period on site at TAM, leading up to a tape-cutting ceremony that was held on the day the aircraft was officially welcomed to the fold and exhibited publicly for the first time.

The T-1B displayed today at the Tokorozawa Aviation Museum is seen here in a hangar at

The T-1B displayed today at the Tokorozawa Aviation Museum is seen here in a hangar at

its Ashiya home base in September 2000, during its time with the 13th FTW.

(2) Exhibits Hanging in Suspended Animation (in order they appear to visitors entering main exhibition hall from entrance lobby)

(Photo: November 2019)

(Photo: November 2019)

(15) Stinson L-5E Sentinel (True identity unconfirmed, possibly former JGSDF 10303, exhibited since April 1993 opening)

Little is known about the motley collection of 35 or so L-5s—in four variants—that were supplied to the JGSDF’s predecessor, the Hōantai (National Safety Force, NSF) in 1953. Some sources state that this L-5E (reportedly ex-U.S. Army 44-17725, which became JG-10303) might even have been delivered in 1952 and thus would have seen service with the Keisatsu Yobitai (National Police Reserve) prior to the NSF’s formation on August 1 of that year. All surviving examples were withdrawn in 1957–58, whereupon ‘10303’ was placed in storage at Kisarazu and given occasional airings at base events before being one of several aircraft given suspended sentences at Tokorozawa. At some stage, the aircraft was painted as L-5G 535025.

(Photo: April 2017)

(Photo: April 2017)

(16) Kawasaki-Hughes OH-6J (30165, exhibited since April 1993 opening)

This aircraft’s active service spanned 15 years, from its delivery on March 14, 1974, to its withdrawal from use when with the 8th AvSqn at Takayubaru Army Camp (adjacent to Kumamoto Airport) on February 15, 1989.

(Photo: May 2013)

(Photo: May 2013)

(17) Kawasaki KAL-2 (20001, exhibited since April 1993 opening)

One rarity is the Kawasaki KAL-2 liaison aircraft, which was first flown in November 1954 to fulfill a then Japan Defense Agency requirement but lost out to the Fuji LM-1 version of the T-34A Mentor. One of only two built, it was initially delivered to the JASDF as 40-1555 on December 23, 1954, and evaluated at Gifu before being passed to JGSDF ownership and flown from Akeno in 1964. This aircraft was also rescued from storage at Kisarazu for permanent display at Tokorozawa.

(Photo: May 2013)

(Photo: May 2013)

(20) Fuji-Bell UH-1B (41547, exhibited since April 1993 opening)

The resident UH-1B was originally handed over to the JGSDF on July 11, 1969, and served with the branch of the aviation school at Kita-Utsunomiya but was with the Northeastern Region Helicopter Squadron when retired from active service on June 29, 1987.

(Photo: May 2013)

(Photo: May 2013)

(19) Fuji-Beech T-34A Mentor (60508, exhibited since April 1993 opening)

Nine Fuji-built T-34As were transferred from the JASDF to the JGSDF during the course of 1964. Manufactured and delivered to the JASDF as 51-0346 in March 1955, the example on display at Tokorozawa was received by the JGSDF on May 11, 1964. Withdrawn from use on May 6, 1973, the aircraft was also among those placed in storage at Kisarazu.

(Photo: April 2017)

(Photo: April 2017)

(21) Piper L-21B Super Cub (12032, exhibited since April 1993 opening)

Another aircraft given a new lease of life after having been in long-term storage at Kisarazu Army Camp for the Tokorozawa project was one of the 62 L-21Bs that the U.S. Army had originally been supplied to the JGSDF’s predecessor, the Hōantai (National Security Force) in 1953. This aircraft was assigned but presumably never wore the U.S. Army serial 53-3773.

Adjoining Exhibition Rooms

Four “hangar” doors, marked ‘1’ to ‘4’, lead off from the main exhibition hall.

The star of the show in this the “Hangar” exhibit has to be the showcase containing the sole surviving fuselage of a 1930s-vintage Nakajima Type 91 Fighter. As detailed in the Aviation History section of this website, this valuable relic was certified by the Japan Aviation Association as the joint first Important Aviation Heritage Asset on March 28, 2008, and received recognition under the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry’s Heritage of Industrialized Modernization certification programme for fiscal 2008 (actually awarded on February 6, 2009).

Too detailed to include here, the flow chart on the left of the Type 91 information poster uses Japanese fighters to illustrate the transition periods in Japanese aircraft production. These are given in terms of manufacturing (under licence, designs invited from overseas, Japanese designs); wing configuration (biplane, high-, mid- or low-wing), and by chief designer (Koyama, Horikoshi, Doi).

Not real but imposing nonetheless is the replica of a Nieuport 81 with the apt and authentic registration

Not real but imposing nonetheless is the replica of a Nieuport 81 with the apt and authentic registration

J-TECH. Originally operated by the Imperial Japanese Army, many of this type found

their way to civilian ownership. (Photo: November 2019)

(Photo: November 2019)

(Photo: November 2019)

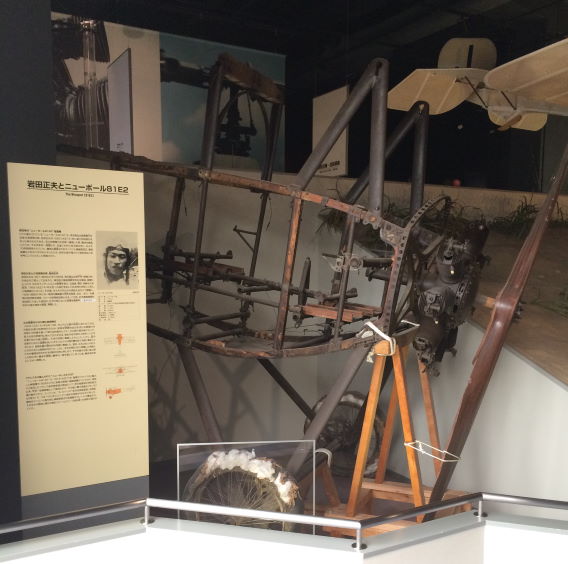

To the left of the “Nieuport” is all that remains of the airframe from the real Nieuport 81E2 J-TECH (above), as is explained on the accompanying panel:

|

Masao Iwata and Nieuport 81E2 |

||

|

Jikō Temple Nieuport 81E2 Biplane place of his birth, the village of Tokikawa in the Hiki district of Saitama Prefecture, in 1926 [Aug. 16].

Saitama-born Civilian Pilot Masao Iwata Masao Iwata was born on December 2, 1901, as the third son of a landowner from the village of Taira

Flight to Attend Father’s Memorial Service and Visit Home On August 13, 1926, the very day that marked the first O-Bon Buddhist event since his father’s death,

Imported from France: Nieuport 81E2 A training aircraft imported from France by the Imperial Japanese Army in 1918, the Nieuport 81E2 |

||

Serving to point the way to the entrance to other exhibits on the ground floor are two panel displays, on the birdman Kokichi Ukita (1757–1847) and the aviation pioneer and inventor Chuhachi Ninomiya (1866–1936). The stand-alone displays show two of Ninomiya’s flying machine designs, the Crow (left) and Jewel Beetle—the subject of the large drawing on the main panel—which date from the 1890s.

The route leads visitors through a low-lit corridor containing “shutter” display panels flanking windows overlooking brightly lit dioramas of scenes from Japanese aviation history, photos and models. The first panel on the right sets a sombre tone:

| 日本最初の航空殉職者 Japan’s First Aviation Casualty* |

||

|

Disaster Befalls First Lieutenants Kimura and Tokuda

An Era When Flying Was Inherently Dangerous To a great extent subject to the vagaries of the weather, coupled with shortcomings in airmanship and

High-Performance Machine That Suffered Unfortunate Fate The aircraft in which the two men were flying that day was a Blériot XI-2bis that had been imported

|

||

| * Should be ‘Casualties’. The full meaning of the Japanese is ‘first Japanese pilots to lose their lives on active duty’. |

The first window on the left gives an impression of what the Yoyogi Army Parade Ground (today’s Yoyogi Park) in Tokyo was like at the time of the first powered flights by heavier-than-air aircraft in December 1910. (See also the story at the foot of the Aviation History page of this website for more details.)

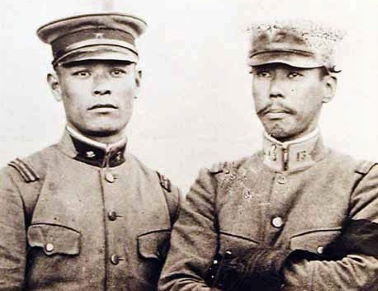

First Lieutenants Kinichi Tokuda (left) and Suzushirō Kimura, the ill-fated Blériot

First Lieutenants Kinichi Tokuda (left) and Suzushirō Kimura, the ill-fated Blériot

crew. Tokuda had turned 28, Kimura’s age, just three days before the crash.

(Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

| 日本初の動力飛行成功 The Success of Japan’s First Power-driven Flights |

||

|

Capts. Tokugawa and Hino’s First Flights in Japan

Flights of French and German Aircraft Both aircraft used for the first flights in Japan had been purchased in and imported from France and

Troublesome Flight Experiments at Yoyogi Parade Ground Those first flight experiments in Japan were beset with a series of problems from the preparatory stages, |

||

The shutter on the right side shows a diagram of the then Yoyogi Army Parade Ground (with the locations of Meiji Shrine at the top, the then hangar below and to the right, and Harajuku Station on the extreme right) and the following text:

| Actual Test Flight of December 19, 1910

In the book Nihon Kōkū Kotohajime (The Beginnings of Japanese Aviation), published in 1964 [the Having completed the aircraft’s flight preparations, as a preliminary manoeuvre I started taxying from

Flight time: Three minutes Distance: 3 km Height: 70 metres Takeoff distance: 30 metres |

||

|

国産機の初飛行 The First Flight of Self-Manufactured Civil Plane* |

||

|

Sanji Narahara and Narahara No. 2 Aircraft Six months prior to this maiden flight, he had completed his Narahara No.1 and flight tested the aircraft

The Early Days of Japanese Aircraft Development The Osaka antique dealer Shinzō Morita [1879–1961] produced a copy of a Blériot monoplane that was In addition, other aircraft that were built and on which patents were taken out at patent offices at that

First Domestically Produced Aircraft for Which Tractor Configuration Adopted

Shinzō Morita and His Self-Built Monoplane From Europe, the Osaka trading merchant Shinzō Morita brought back with him to Japan a |

||

|

* The wording that appears on the display panel (November 2019). A more accurate translation would |

(From left to right) Sanji Narahara, the Narahara No. 2 and the Narahara No. 4 Ōtori

(From left to right) Sanji Narahara, the Narahara No. 2 and the Narahara No. 4 Ōtori

Shinzō Morita (1880–1961, in white boater hat) and team in front of his aircraft at the Joto Parade

Shinzō Morita (1880–1961, in white boater hat) and team in front of his aircraft at the Joto Parade

Ground, Osaka, in 1911. A self-built cross between a Blériot and an Antoinette, the aircraft was

flown from the same location in April 1911. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Taken from the Osaka Mainichi Shimbun for April 25, 1911, the newspaper cutting at the foot of the panel contains another photo of the intrepid pilot Morita, who had by chance trained with Army captains Hino and Tokugawa in France. By then short of money, he had brought only the engine, a propeller and some blueprints (all of which had cost 13,000 yen) back to Japan, where he hired a team of local Osaka artisans (above) to assist in (literally) getting the project off the ground.

Continuing along the left-hand wall you will come to a panel (above) of more than 100 aircraft photos—against a blueprint of an Army Type 95 Fighter (Kawasaki Ki-10)—and a five-aircraft model display on Aircraft Development, crowned by a photo of an airship. Colour-coded to indicate air arm (Army green, Navy blue,) or civilian (yellow), the 11 columns of aircraft photos are arranged by operator and mission (from left): Army and Navy fighters; Navy and Army bombers; Navy attack aircraft; Army main reconnaissance aircraft; Navy reconnaissance aircraft; Navy flying boats; civilian aircraft and civilian transports; Navy training aircraft.

The Army airship was originally the Walserwald, one of six imported from Germany in June 1912. Damaged in an accident on March 28, 1913, repair and modifications to the renamed Yūhi (Great Leap) were commenced at Tokorozawa in late August 1914 and followed by her commissioning in April the following year. Despite all those efforts, her short-lived career ended with decommissioning in July 1917.

A translation of the accompanying white panel to the left of this display is as follows:

| 日本の航空機開発の歴史 [History of Japanese] Aircraft Development |

||

|

Formed in 1909, the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group completed the Kaishiki Ichi-Gō aircraft In 1913, the Army started domestic production of Renault 50hp engines at its artillery arsenal and the Between 1919 and 1924, a number of what were later to become famous aircraft and aero-engine

From Import of Technology to Establishment of Independent Technologies Japanese aircraft development started with the acquisition of technologies from the advanced aviation From the latter half of the 1920s, engines were of foreign manufacture, but to satisfy the performance |

||

(Photos: November 2019)

(Photos: November 2019)

Gracing the end wall of this zone is a splendid photo of Aichi AB-1 J-BAKL (above). Completed as a landplane in April 1928, this aircraft saw brief service with Japan Aviation Co., Ltd. but was then converted to a seaplane. Transferred to Tokyo Air Transport, the aircraft plied the route between Tokyo’s Haneda airport and Shimoda as well as Shimizu in Shizuoka Prefecture until 1936. The chronology shows milestones and important dates in Japanese civil aviation from 1922 to 2000. A translation of the white panel to the left is provided below.

| 日本の航空運送歴史 [History of Japanese] Air Transportation |

||

|

The Beginnings of Japanese Air Transportation In 1922, Nippon Air Transport Service was founded and commenced regular air services carrying mail The start of full-scale passenger-carrying air transport services came in 1927, the very first services

Popularization of Private Use of Aircraft As the passenger aircraft of that time were slow, and cabin air-conditioning and soundproofing had yet Then called “air girls”, the first cabin attendants in Japan appeared and in-flight services commenced

From License-built to Japanese-built Transport Aircraft Starting with examples sold off as military surplus, the civil transport aircraft used at that time were |

||

The propellers displayed in a showcase close to the Nakajima Type 91 are from (left) a 1920s Army

The propellers displayed in a showcase close to the Nakajima Type 91 are from (left) a 1920s Army

Type Kō-1 Trainer (Nieuport 81) and, donated from the JGSDF, a Cessna L-19 Bird Dog. Those in

the photo are (top row, left to right): an early experimental propeller with swept-back blades

(1909); a wooden type covered in brass for protection from enemy attack (1919); and a

variable-pitch propeller (1928). (Bottom row, left to right): An early screw-type

wooden propeller (1893); a propeller developed by the Wright Brothers for

wind-tunnel experiments (1909); and a seaplane propeller, also covered in

brass for protection from rust (1917)

On wood-paneled walls, the next two contrasting exhibits cover the Wright Brothers’ short-hop successes and the numerous long-distance flights that were ostensibly spawned from those events in North Carolina in December 1903. The only Japanese content here is the first successful trans-Pacific flight, from Misawa in Aomori Prefecture to Wenatchee in Washington, which was completed by the American duo Clyde Pangborn (1895–1958) and Hugh Herndon (1899–1950) in the Bellanca CH-400 Skyrocket Miss Veedol in October 1931.

Upper Level Exhibits/Panel Displays

Naturally, one area is devoted to providing the visitor with detailed information about Tokorozawa`s important contribution to Japanese aviation and to the pioneers who made it possible.

Tokorozawa Memorial Gallery (The History of Tokorozawa)

Although this appears like the main entrance to the Tokorozawa Memorial Gallery, the exhibits are

Although this appears like the main entrance to the Tokorozawa Memorial Gallery, the exhibits are

arranged chronologically from the other entrance, opposite the suspended Stinson L-5E.

Covered in polythene, it seems that someone has recently picked up the summer and

winter flying uniforms (right) from the dry cleaners. (Photo: November 2019)

Following the sequence of the red numbers used in the Hangar section of the previously mentioned audio guide, this part of the J-HangarSpace coverage is designed to accompany the visitor through this maze of fascinating displays while providing additional information on selected items of particular interest. To avoid any confusion and as an additional aid to navigation, the occasionally inaccurate English in the individual section titles in this zone appears as it does on the panels.

軍用機の宝庫 航空参考館

Military Aircraft Treasure House: Aviation Reference Hall

(Photo: February 2020)

(Photo: February 2020)

Not covered in the audio guide, this showcase contains a 1/144-scale diorama of Tokorozawa, indicating the location of a building that once housed its first aircraft collection.

The map on the far left shows the former Tokorozawa airfield at the top and the location of the Aviation Reference Hall circled at the bottom. The Army aerial photo, dated September 1944 to the map’s right, verifies the presence on the airfield even then of a giant Type 92 Heavy Bomber (Ki-20), which was a variant of the Junkers G.38 and dated back to the late 1920s. A translation of the left panel follows.

|

東洋一の航空博物館だった航空参考館 (Aviation Reference Hall Was Foremost Aviation Museum in the East) |

||

| In 1921, the site of a materiel warehouse for the Tokorozawa sub-division of the Army Aviation Department’s Supply Branch was completed at Tokorozawa station’s west exit. As the site, which covered 5.5 hectares (13.5 acres), was situated to the south of the at that time Army’s Tokorozawa airfield (today the Tokorozawa Aviation Memorial Park), it was known as the South Warehouse. The South Warehouse was also directly adjacent to Tokorozawa station, and aircraft, equipment and materials were carried from the station along a dedicated railway siding [shown in the diorama, next to the Ki-20] for housing in the warehouse. In 1923, the South Warehouse, which until that time had only been of wooden construction, was In 1935, the former South Warehouse [shown with two aircraft parked in front] became the site for The Aviation Reference Hall was established at the South Warehouse as an exhibition facility for After the war and up until 2000, the Seibu Railway Company had used the site for the manufacturing |

||

The caption of the Type 92 Heavy Bomber model states that the immense aircraft had a wingspan of 44 metres (144 feet), a little more than that of a B-29. As the aircraft was too large to be stored in the hangar, at that time it was placed outside. In this diorama, the positioning of this aircraft model is shifted due to the display space, but the arrangement at that time can be confirmed by the aerial photograph contained in the description on the left wall panel.

A Type 92 Heavy Bomber at Hamamatsu airfield, Shizuoka Prefecture

A Type 92 Heavy Bomber at Hamamatsu airfield, Shizuoka Prefecture

(Photo [undated] via Wikimedia Commons)

The top half of the right panel is given over to six photos of aircraft that were exhibited at the Aviation Reference Hall. Clockwise from the top right: Kō-4 (Type 1, Model 4) Fighter (Nieuport-Delage NiD.29); Tei-2 (Type 4, Model 2) Bomber (Farman F.60); Junkers Ju87 dive bomber; Type 92 Heavy Bomber (Junkers-Mitsubishi Ki-20); Type 88 Reconnaissance Aircraft; and a 1910 Henri Farman. The note below the photos states that other aircraft exhibited included the prototype of the Kawasaki Ki-5 fighter, a Kellett K-3 autogyro as well as Russian Polikarpov I-15 and I-16 fighters.

A translation of the lower text on the right panel follows.

|

南倉庫の記憶 (South Warehouse Recollections) |

||

| Born in 1923, from 1938 Kei-ichi Iwada was assigned to the Army Aviation Officer Academy Materials Factory, where he repaired and maintained all types of Army aircraft, including the Type 95-1 (Ki-9) trainers [pictured below] that he worked on at the South Warehouse. Valuable recollections of the South Warehouse are spelled out in the notes he wrote. At that time, the South Warehouse was extolled as being “the foremost aviation museum in the East,” and it seems that the aircraft-related items were piled up so high that there was no place to display them, so it really was a treasure trove of military aircraft. |

||

An Army-surplus Ki-9 trainer from an unidentified civilian flying school

An Army-surplus Ki-9 trainer from an unidentified civilian flying school

(Photo [undated, location unknown] via Wikimedia Commons)

収蔵資料展示

(Display of Collected Documents)

Particularly difficult to photograph on account of the many reflections, the items on display in the opposite showcase all relate to the Army Otsu-1 (Type 2, Model 1) Reconnaissance Aircraft (Salmson 2A2).

(Photo [undated, location possibly Tokorozawa] via Wikimedia Commons)

(Photo [undated, location possibly Tokorozawa] via Wikimedia Commons)

The in-flight photo of a formation of this type over Tokorozawa, which provides a splendid backdrop, was taken in 1926 by Hideo Kitagawa, of whom more later. In the top left-hand corner of the display case is a description of the aircraft, a translation of which follows.

|

Army Otsu-1 Reconnaissance Aircraft (Salmson 2A2) Provided Sterling Service at Tokorozawa Airfield in Taisho Era |

||

| Based on the theme of this museum’s collected materials, this section showcases those covering the Army Otsu-1 Reconnaissance Aircraft (Salmson 2A2), around 600 of which were produced, the largest number in Taisho era Japan. Produced in France by the Salmson company, the framework of the fuselage and wings of this single- In addition to having been utilized for instruction at Tokorozawa airfield for the French Aviation Taken at Tokorozawa airfield from the Taisho era to the early Showa era, many photos remain of this |

||

| Wingspan: 11.76 metres | Weight, empty: 950kg |

| Length: 8.624 metres | Weight, equipped: 1,500 kg |

| Max. speed: 182km/h | Endurance: approx. 3 hours |

| Engine: Nine-cylinder, liquid-cooled Salmson radial | |

At the front of the showcase is one of those propellers, with a propeller hub and wing strut. The caption to the piece of wing fabric states that, as the power outputs of the engines of that time were low, wings were made not of metal but of wood, over which fabric was stretched, with the aim of reducing weight.

To the top right is a technical drawing of a Salmson, donated by Kawasaki designer Takeo Doi, about whom we will also be hearing more later.

所沢飛行場の歩み

(1) The Tokorozawa Airfield Past to Present

The Perspex panel on the right states:

|

From the time when the Wright Brothers accomplished [what is widely regarded as] the world’s first |

||

Alongside selected details of social conditions and key events, which are cited from as far back as 1877, the wallchart provides details of Tokorozawa airfield’s history from 1911 and, postwar, up to the opening of the museum in April 1993.

Many of the dates concerning Tokorozawa have already been mentioned, so will not be repeated here. Of the additional details provided, perhaps the most interesting are those detailing the airfield’s gradual expansion, the last phase of which was completed in 1944, and the three-stage reversion of land used as a U.S. Army base to Japanese ownership and conversion to parkland. The last poignant wartime entry is that for June 1945, when a tokkōtai (special [suicide] attack) unit was formed.

| Oct. 1913 | Balloon unit [that had formed in Oct. 1907] moves from Nakano, Tokyo, to Tokorozawa |

| Aug. 1914 | Provisional squadron formed and sent to Shandong province, China. First involvement in air combat |

| Feb. 1915 | 1913 model Maurice Farman departs on first mail flight (Tokorozawa to Shizuoka, Nagoya and Osaka) |

| Dec. 1917 | Second phase of airfield construction completed. Airfield area increased by 115 hectares (285 acres) to around 190 hectares (475 acres) |

| Mar. 1936 | Third phase of airfield construction completed. Airfield area increased by just over 50 hectares (130 acres) to around 245 hectares (600 acres) |

| Mar. 1944 | Fourth phase of airfield construction completed. Airfield area increased by around 120 hectares (300 acres) to around 365 hectares (900 acres) |

| June 1971 | Equivalent to 60% of its total area, 192 hectares (475 acres) returned to Japanese ownership |

| Mar. 1978 | Start of joint use with Aviation Memorial Park |

| June 1978 | Additional nine hectares (24 acres) returned |

| June 1982 | Final hectare (three acres) returned |

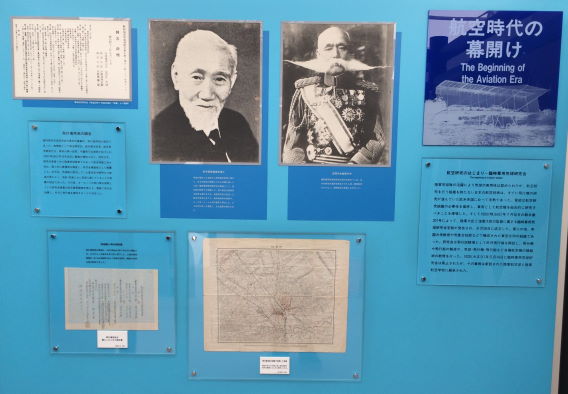

航空時代の幕開け

(2) The Beginning of the Aviation Era

[Four panels]

(Photo: April 2017)

(Photo: April 2017)

Here, the Perspex sign (text given below) outlines the rising interest in ballooning. To its left is a wooden sign, bearing the Japanese for Balloon Squadron, which thus dates back to the earliest days of Imperial Japanese Army aviation.

|

[Panel 1/4] 気球熱の高まり The Increased Interest of [sic] Ballooning |

||

| For a battle in southwest Japan, which had commenced on February 15, 1877, the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy produced a tethered balloon to contact government forces surrounded within Kumamoto Castle by the army of [Takamori] Saigō [during the Satsuma Rebellion]. At 08:00 on May 21 that same year [too late for the siege, which had been lifted on April 12], trials were conducted on the Academy’s Tsukiji Naval Training Ground in front of the Department of the Navy [in Tokyo], during which the balloon rose to a height of 110 metres. This was the first flight made by a Japanese aircraft. Thereafter, steady progress was made in balloon research, and an Army Balloon Unit formed in 1907 as Japan’s first standing air squadron. Japan’s aviation era thus started with balloons. |

||

The highly decorated soldier is Maj. Kumao Tokunaga (1873–1946), an Army engineer who was the Balloon Unit’s second commanding officer, from March 1908 to May 1914, and thus oversaw the unit’s move from Nakano, Tokyo, to Tokorozawa in October 1913.

The text that accompanies the three balloon photos on the left panel is as follows:

|

初の航空部隊―陸軍気球隊 |

||

| During the Russo-Japanese War that broke out in 1904, Japanese forces came up against the fortress in Lushun (Port Arthur, now Dalian in Liaoning province, China), which was said to be impregnable. To conduct reconnaissance, the Army had formed a Provisional Balloon Squadron within the Signals Training Battalion in Nakano, Tokyo. This was the first occasion on which balloons had participated in a combat zone. The Balloon Squadron was disbanded at the end of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, but now aware of the importance of balloons in the field the Army formed a Balloon Unit, again within the Nakano-based Signals Training Battalion, and commenced training that same year. On October 9, 1907, the Balloon Unit was reformed and officially named the Army Balloon Unit, thereby becoming Japan’s first standing air unit. Its main roles were observation and reconnaissance/communications—for which tethered and free balloons, respectively, were used—but these roles were assumed by the Training Department of the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group that was formed subsequently. From the time of its establishment as the Provisional Balloon Squadron, the Army Balloon Unit had been operating from Nakano, but as the site was proving inadequate due to the expansion of the scale of operations, the move to Tokorozawa was carried out in October 1913. |

||

The three balloons are, from top to bottom:

Balloon Manufactured by Major Tokunaga

This balloon was trialed at an engineering conference by Army engineer Maj. Kumao Tokunaga (seen in the lower right photo of these panels) in December 1901. With Tokunaga himself on board, the balloon was taken up to a height of 500 metres, from where he undertook aerial photography and used a telephone to relay reconnaissance reports. This led to the Army top brass present recognizing the practicalities of using balloons for military operations.

Yamada Kite Balloon

A balloon manufactured by Inosaburō Yamada [1864–1913], who at that time was Japan’s sole balloon manufacturer. During the Russo-Japanese War [1904–1905], two balloons of this type made up the Provisional Balloon Squadron, which acquitted itself well during the reconnaissance mission to Lushun (Port Arthur).

The First Japanese Aircraft

A manned tethered balloon jointly manufactured by the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Naval Academy and the Army’s Technical University. The balloon’s air sac, which was made of bonded high-quality Japanese paper (large format, thick paper), was filled with hydrogen. It was made for use against the Satsuma Rebellion [1877], which had ended before its practical value could be determined, so the balloon was never used in actual combat.

(Photo: April 2017)

(Photo: April 2017)

|

[Panel 2/4, right] 航空研究の始まり— 臨時軍用気球研究会 The Beginning of Aviation Studies: Provisional Military Balloon Study Group |

||

| The operational feasibility of balloon operations was confirmed through the efforts of the Army Balloon Unit. However, as the country lacked an organization to conduct research, Japan’s aviation technology was rudimentary in comparison with the West, where countries were already making advances with aircraft research. The need for an aviation research organization was keenly felt by the military authorities, who advocated general research into aircraft for military use. Under Imperial Edict No. 207, dated July 30, 1909, [displayed on the top left of this panel], a provisional government-regulated organization for military balloon research under the supervision of the ministers for the Army and Navy was promulgated and established on August 28 that year. This was a joint military-governmental organization that, in addition to military men, was made up of professors from the Imperial universities and engineers from meteorological observatories. The Study Group having established Tokorozawa airfield as its flight testing ground, the manufacture of aircraft and airships as well as flight and technical training on all types of aircraft, such as balloons, aircraft and airships, were conducted here. The Provisional Military Balloon Study Group was disbanded on May 14, 1920, and its duties passed to the then recently established Army Department of Aviation and Army Flying School. |

||

Sporting his trademark propeller moustache is Army Lt. Gen. Gaishi Nagaoka (1858–1933), who was the first head of the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group. He was instrumental in establishing the basic foundations of not only military but also civil aviation in Japan.

Pictured on the left is physics expert Aikitsu Tanakadate (1856–1952), who as a member of the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group was heavily involved with Japanese aircraft research from its infancy. Himself the founder of a research institute, outside of aviation he was active in geophysics and also advocated the adoption of the Roman alphabet and the metric system.

Additional information can be gleaned from the top Perspex sign on the left (with no English title), which deals with the surveys of candidate sites for an airfield. One of the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group’s first tasks, the survey process was commenced on October 28, 1909. That December, having carried out personal inspections, the aforementioned Maj. Kumao Tokunaga recommended Tokorozawa and was supported from the scientific standpoint by Study Group member Tanakadate, who had visited airfields in Europe and sent a telegram giving Tokorozawa his vote.

The large map was used by Maj. Tokunaga and Army engineer Shūhei Iwamoto (see Panel 4) for their survey in December 1909, and bottom left is a receipt from the time of the land acquisition. That process was commenced on April 15, 1910, and completed only four months later, on August 12. The prices paid for around one hectare (2.5 acres) were 300 yen for residential land and 100 yen and 80 yen for farmland and woodland, respectively.

(Photo: April 2017)

(Photo: April 2017)

|

[Panel 3/4, right (not shown)] 飛行機はヨーロッパで (Aircraft Purchased in Europe) |

||

| The location for building an airfield may have been decided, but at that time Japan did not possess a single aircraft and, of course, had no pilots either. So that they could receive pilot training and purchase aircraft, the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group sent two of its members to Europe in April 1910; Yoshitoshi Tokugawa and Kumazō Hino were Army captains in the engineers and infantry, respectively. Having both undergone flight training in France and Germany, they purchased a total of four aircraft and returned to Japan in October of that year. |

||

The accompanying photos here show Capt. Kumazō Hino (left panel), who purchased a Grade monoplane and a licence-built Wright biplane in Germany, outnumbered by Tokugawa-related exhibits. The latter’s Aéro-Club de France pilot’s licence (No. 289, issued on November 8, 1910) and favourite flying helmet appear next to a group photo of Tokugawa and the host family with whom he lodged close to the Farman Flying School. He reportedly graduated with all of one hour’s flight time on Farman biplanes, of which only 15 minutes were solo. He had only received training on taxying a Blériot XI-2bis, the other type of aircraft he was to order, when the time came for him to return to Japan.

The caption to the lower photo, entitled Aircraft Haulage, states that two of the four aircraft purchased, Tokugawa’s Henri Farman and Hino’s Hans Grade, arrived at the Port of Yokohama [in Kanagawa Prefecture] on November 30, 1910. They were then brought by ship to Shinagawa [in Tokyo] for unloading before being transported by road on a flatbed cart to the Balloon Unit in Nakano. As the roads at that time were narrow and the road surfaces poor, it is said that transporting the aircraft was beset with difficulties. [The photo shows the Henri Farman container being manhandled en route to Nakano].

Slightly delayed, the Blériot and the Wright aircraft arrived in March 1911.

(Photo: April 2017)

(Photo: April 2017)

|

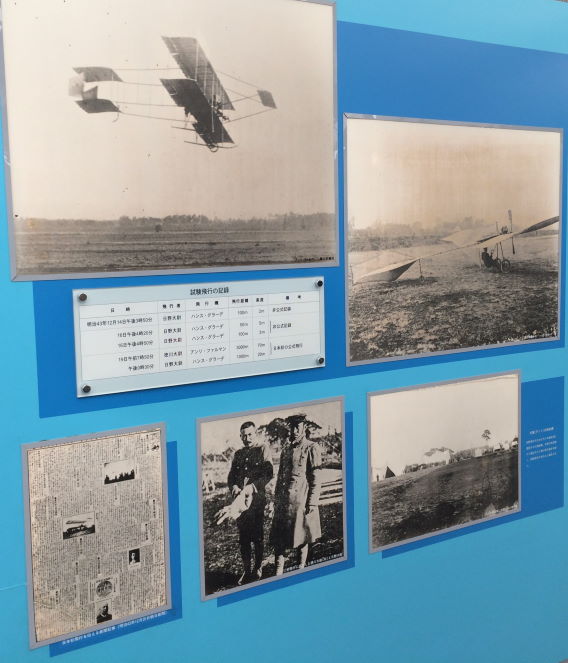

[Panel 4/4, right (not shown)] 日本最初動力飛行 Japan’s First Power-Driven Flight |

||

| When the Henri Farman and Hans Grade aircraft arrived in Japan, the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group conducted experimental flight testing from the Yoyogi Army Parade Ground in Tokyo. It was the Hans Grade piloted by Capt. Hino that succeeded in making the first flight in Japan, on December 14, 1910. However, as this was achieved during taxy trials, this was classed as an unofficial flight. The following day, both aircraft were damaged when taxying, and the Henri Farman needed time for repairs and thus did not fly on either December 15 or 16. Having only required one day for its repairs, the Hans Grade once again succeeded in flying on December 16, but this too was deemed unofficial. On December 17 and 18, strong winds prevented any flying, resulting in a further postponement to December 19, when both aircraft succeeded in making the first officially recognized flights in Japan. |

||

Next to photos of the two protagonists and their aircraft, a chart sets out the sequence of events:

| Experimental Flight Record [December 1910] | |||||

| Date/Time | Pilot | Aircraft | Distance | Height | Remarks |

| 14th, 15:50 | Hino | Grade | 100m | 2m | Unofficial |

| 16th, 16:20 | Hino | Grade | 50m | 5m | Unofficial |

| 16th, 16:50 | Hino | Grade | 100m | 3m | |

| 19th, 07:50 | Tokugawa | Farman | 3,000m | 70m | First official flights |

| 19th, 12:30 | Hino | Grade | 1,000m | 20m | |

Displayed underneath the chart are (from left) pages from the December 20, 1910, edition of the Asahi Shimbun; the two pilots (Hino on the left); and the tent-type hangars erected on the Yoyogi Army Parade Ground for the aircraft. Having been brought across from Nakano by the Balloon Unit, they were dismantled after the conclusion of the experimental flights.

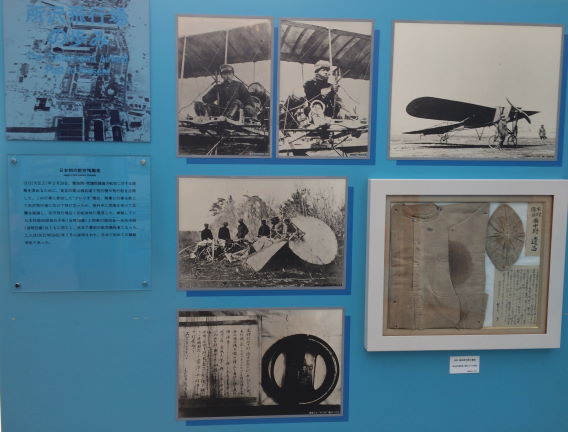

日本最初の飛行場

(3) Japan’s First Airfield

[Two panels]

(Photo: April 2017)

(Photo: April 2017)

|

[Panel 1/2] 所沢飛行場の開設 Establishment of the Tokorozawa Airfield |

||

| On April 1, 1911, the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group’s Tokorozawa Testing Ground was completed, and Tokorozawa airfield, Japan’s first, officially came into existence. At the time of its opening, the airfield covered an area of 76.3 hectares [190 acres], and a runway 400 metres long and 50 metres wide had been prepared. At that time, the Group’s fleet comprised four aircraft: the Henri Farman and Hans Grade that had recorded the first flights from the Yoyogi Army Parade Ground the previous December, and the Blériot and Wright aircraft that had only arrived in Japan the previous month. The airfield’s facilities were also rudimentary. |

||

The top left of the upper group of photos shows oxen pulling a cart laden with a crated aircraft from Tokorozawa station to the airfield. Then, clockwise, there is a photo of each of the first four types that were based there: the Henri Farman and Hans Grade as well as the Blériot and Wright aircraft.

The text beneath the bottom left photo, which shows the observatory, is translated below. The captions on the other two photos just say ‘Tokorozawa airfield at the time of its establishment.’

|

開設当時の施設 |

||

| In the vicinity of the runway were a steel-framed aircraft hangar that could house four aircraft, a three-storey observatory and a fuel storage depot. The observatory mainly carried out weather observations and thus heralded the start of meteorology for aviation purposes in Japan. |

||

(Photo: April 2017)

(Photo: April 2017)

|

[Panel 2/2] 所沢飛行場での初飛行 |

||

| The Provisional Military Balloon Study Group carried out the first flight practice from April 5–15, 1911. At 05:37 on the first day, the Henri Farman piloted by Capt. Tokugawa was flown for a distance of 800 metres at a height of 10 metres; this was the first flight from Tokorozawa airfield. Due to the first aircraft flights in Japan having only taken place in December of the previous year, despite the earliness of the hour hordes of uninvited spectators descended on Tokorozawa. Thus a viewing gallery was set up on the west side of the airfield, and each person charged 10 sen [one tenth of a yen] for a seat. The presence of stalls selling food loaned the event an atmosphere akin to a noisy festival. |

||

Once again, a chart is provided, this time to record the 14 flights carried out during the first flight practice period at Tokorozawa, only four months after those very first flights in Tokyo. Not surprisingly, these included two “firsts” and soon set Japanese flight duration records tumbling.

| First Flight Practice Record [April 1911] | ||||||

| Date, Time | Pilot | Aircraft | Distance | Height | Duration | Note |

| 5th, 05:37 | Tokugawa | Farman | 800m | 10m | 1m 20sec | (1) |

| 06:25 | Hino | Wright | 3,000m | 50m | 3m 30sec | |

| 06:40 | Hino | Wright | 17,500m | 142m | 18 min | |

| 6th, 06:15 | Tokugawa | Blériot | 5,000m | 50m | 4m 50sec | (2) |

| 7th, 06:04 | Hino | Wright | 7,800m | 200m | 11m 30sec | |

| 8th, 05:15 | Tokugawa | Blériot | 30,400m | 180m | 31m 40sec | |

| 06:25 | Tokugawa | Blériot | 8,200m | 100m | 7m 40sec | |

| 9th, 05:20 | Hino | Wright | 61,700m | 230m | 53 min | (3) |

| 06:39 | Tokugawa | Blériot | 8,300m | 60m | 8m 5 sec | |

| 07:30 | Tokugawa | Blériot | 5,500m | 40m | 4m 50sec | |

| 13th, 05:42 | Tokugawa | Blériot | 79,600m | 250m | 69m 30sec | (4) |

| 14th, 05:20 | Tokugawa | Farman | 3,500m | 35m | 3m 40sec | |

| 05:45 | Tokugawa | Blériot | 35,700m | 320m | 32 min | |

| 15th, 06:27 | Tokugawa | Blériot | 14,000m | 30m | 11 min | |

Note 1: First flight from Tokorozawa airfield

Note 2: First two-man flight in Japan

Note 3: New Japanese record for longest flight in a Wright aircraft

Note 4: New Japanese record for longest flight in a Blériot aircraft

Surrounding the chart, in clockwise order from the top, are photos of: A Henri Farman over Tokorozawa; the flight of a Blériot; a Wright; and the main gate of the airfield alongside a newspaper account of events from the April 6, 1911, edition of the Asahi Shimbun.

所沢飛行場の歩み

(4) The Tokorozawa Airfield Past to Present

[Seven panels]

(Photo: November 2019)

(Photo: November 2019)

|

[Panel 1/7] 初の国産軍用機―会式一号機 Japan’s First Self-Manufactured Military Aircraft [the Kaishiki Ichi-Gō] |

||

| Tokorozawa airfield having been established, the stage was reached at which flight training could be conducted frequently. The four aircraft had been worked hard, however, and the wear and tear they sustained extensive. Capt. Tokugawa was fully aware of the aircraft’s shortcomings and in April 1911 began the design of a new aircraft as part of his duties with the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group. The design was based on the 1910-model Henri Farman, but improvements were devised, such as in terms of the airframe’s structural strength, climbing performance and speed. [Some contemporary technical drawings are displayed on the bottom right side of this panel.] Constructed in the hangar at Tokorozawa from July that same year, Japan’s first indigenously produced military aircraft—the Kaishiki Ichi-Gō (short for Provisional Military Balloon Study Group Model No. 1)—was completed at the beginning of October 1911. Test flights were conducted at Tokorozawa on October 13, and the favorable speed of 72 km/h and a height of 85 metres successfully attained. |

||

The main accompanying photo shows the Kaishiki Ichi-Gō, and Capt. Tokugawa is seen at the aircraft’s controls in the top right photo. A translation of the text beneath the photo is provided below.

|

“会式一号”機と徳川大尉 (The Kaishiki Ichi-Gō Aircraft and Capt. Tokugawa) |

||

| The Kaishiki Ichi-Gō was constructed under the supervision of Capt. Tokugawa. All the materials were sourced and procured in Japan, but as there were no suitable machine tools available, the wood was processed using saws. Also, the standard of engineering in Japan at that time was low, so manufacturing proceeded through trial and error. Completed after many difficulties had been overcome, the Kaishiki Ichi-Gō generally came to be known as the Tokugawa-shiki, because of his great achievements in the aircraft’s design and manufacture. |

||

The text that accompanies the group of four photos provides the following information:

|

次々につくられた“会式機” (Kaishiki Aircraft Produced One after Another) |

||

| The success achieved with the Kaishiki Ichi-Gō having instilled its members with the confidence necessary, the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group developed a succession of new aircraft [actually further variations on the Henri Farman theme]. A total of six more Kaishiki aircraft were built from 1912 to 1916, Model Nos. 2–4 (modified Model No. 1s) being designed by Tokugawa, Model Nos. 5–7 by [Army Engineer and Provisional Military Balloon Study Group member] 1st Lt. Shigeru Sawada. Having been Sawada’s own design, the last of them [and the eighth design], the Kaishiki Model No. 7 Small Aircraft (Kaishiki Model No. 7 Destroyer Aircraft) was Japan’s first indigenously produced fighter aircraft. |

||

The four photos show (from the top left down) the Kaishiki Model Nos. 2, 3 and 5 as well as the Kaishiki Model No. 7 Small Aircraft. Also known as the Kaishiki Model No. 7 Destroyer Aircraft or, more simply, the Sawada-shiki.

Arising from modifications to an imported 1914 Model Henri Farman, the original Kaishiki Model 7 was a reconnaissance aircraft completed in April 1915 but lost in an accident at Tokorozawa that September.

Having commenced work on his own fighter design in the autumn of 1915, Sawada salvaged the original Model 7’s 90hp Curtiss OX-5 engine to power his aircraft. The design drew on the aerobatic Curtiss designs, such as the Model D, which at that time were being imported into Japan.

Designer and builder of Japan’s first indigenously produced fighter, Army 1st Lt. Shigeru Sawada

Designer and builder of Japan’s first indigenously produced fighter, Army 1st Lt. Shigeru Sawada

was to lose his life when test flying the aircraft in March 1917. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Completed on June 11, 1916, the pusher-configured aircraft took to the skies for the first time two days later. Full-scale testing commenced in February 1917, following Sawada’s return from a fact-finding visit to Europe, where he had inspected military aircraft types. Tragically, he lost his life when the aircraft broke up during the pull-out from a dive over Tokorozawa airfield on March 8 of that year.

(Photo: November 2019)

(Photo: November 2019)

|

[Panel 2/7] 日本最初の航空殉職者 Japan’s First Aviation Casualty [sic] |

||

|

[The main, Perspex-covered explanatory text repeats the information (and the mistake in the title) |

||

Next to the main photos of the two pilots at the controls of aircraft, the other images depict the Blériot prior to departure with 1st Lt. Kimura in the background and the crash site. Below is a photo of the aircraft’s control stick that, poignantly, appears with items of the deceased pilots’ personal effects. After the accident, their still bloodstained uniforms were placed on display at the Yūshūkan military museum, the oldest in Japan, located within Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo.

(Photo: November 2019)

(Photo: November 2019)

[Panel 3/7] Continuation of ‘Japan’s First Aviation Casualty’ [sic]

Beneath the section title sign is a grim drawing of the Blériot crash of March 28, 1913, which claimed the lives of 1st Lts. Kimura and Tokuda. The top photos on the opposite panel show the memorials to the two airmen at the crash site (left) and here in the Aviation Park (of which more later). The text is provided below.

|

日本中に衝撃を与えた木村・徳田両中尉の殉職 (The Loss on Active Duty of 1st Lts. Kimura and Tokuda Shocked Japan) |

||

| Following the loss on active duty of 1st Lts. Kimura and Tokuda, the Yamato Newspaper Company erected bronze statues of the two pilots on a commemorative tower at the crash site. Today located here at the Tokorozawa Aviation Memorial Park, the commemorative tower was moved to Tokorozawa airfield in 1929 and moved four more times during World War II. After the bronze statues’ removal from the crash site, a monument was erected in their place. Greatly shocked by the accident, people across the country donated 40,000 yen in cash, in addition to funeral offerings. Posthumously bestowed with meritorious service awards (the Seventh Order of Merit, Senior Sixth Rank), the two pilots were also the recipients of an envelope containing a gift of money from the Emperor Taishō. |

||

The three photos are designed to show the inherent dangers of flying in those pioneering days. Actually, the accident that befell Avro 504K J-BAVF (centre photo) took place some 17 years later, on April 10, 1930. At that time owned by the Gōkoku Hikō Gakkō (Native Land Flying School), the aircraft suffered engine failure over the village of Sunagawa, Ishikawa Prefecture, when being flown by a woman named Atsumi Tamura.

Echoing in part that in the display covering the deaths of Kimura and Tokuda on the lower floor, the text accompanying the three photos states:

|

当時の航空機事故 (Aircraft Accidents at That Time) |

||

| As aircraft at that time were structurally weak and greatly affected by the vagaries of the weather, flying was itself inherently dangerous. As there was also no data on aspects such as airframe durability, and knowledge of airmanship was lacking, small-scale accidents were everyday occurrences. |

||

(Photo: April 2017)

(Photo: April 2017)

|

[Panel 4/7] 所沢飛行場で活躍した飛行船 Airships of the Tokorozawa Airfield |

||

| At the time of the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group’s establishment, the Army had been thinking to expand its fleet of lighter-than air aircraft, such as balloons and airships, as the mainstay of its air arm. There was a feeling that lighter-than-air aircraft were more stable than the still undeveloped [heavier-than-air] flying machines, and it was an age in which they were considered more practical. From 1911 to 1915, the Study Group built three airships, while carrying out experiments and conducting research at Tokorozawa. However, as they were unable to build airships that possessed the practical performance necessary for military operations, in around 1916 the Army gave up on the airship’s future prospects and suspended all research. |

||

The man wearing the imposing hat in the photo beneath the section introduction is Army engineer (and from 1923 Tokyo Imperial University professor) Shūhei Iwamoto (1881–1966). His potted biography reads as follows:

|

岩本周平陸軍教師 (Army Instructor Shūhei Iwamoto) |

||

| As an Army instructor involved in aircraft research from the balloon era, Shūhei Iwamoto contributed to their development. Having played an active role in airship research in particular, he spearheaded the design and manufacture of the I-Gō and Yūhi-Gō (Great Leap) airships. Also involved in instructional activities at the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group and the Tokorozawa Army Flying School, Iwamoto laid the foundations of aeronautical engineering in Japan. Later landing a succession of posts, such as a professorship at Tokyo Imperial University, as a member of staff at an aviation research institute and as chief director of an association of aeronautical engineers, Iwamoto nurtured a host of talented people. |

||

Already encountered atop the photo montage in the history zone on the ground floor, the first airship of the four depicted on the centre of this panel is the Yūhi-Gō (Great Leap).

Yūhi-Gō (Great Leap) Airship

This airship was the result of repairs and redesign work carried out by the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group on the Parseval airship, which had sustained extensive damage [when mooring] at the Aoyama Army Parade Ground (see below). Army engineer Shūhei Iwamoto played a leading design role in the airship’s production, which was carried out in a hangar at Tokorozawa. Work on what was now named the Yūhi-Gō was completed on April 21, 1915. Although powered by the same [three 150hp Maybach] engines as the Parseval, the redesign had brought about improvements in her speed and rate of climb. On January 21, 1916, the at that time revolutionary airship departed on what was planned to be a return flight from Tokyo to Osaka, taking 11 hours and 34 minutes to reach the Shoto Army Parade Ground in Osaka at an average speed of 40 km/h. However, unable to undertake the return leg due to engine problems and strong winds, she was dismantled and ignominiously transported back to the capital by rail. Hardly active thereafter, her last flight was from Tokorozawa to Sendai in Miyagi Prefecture and back on the night of July 21–22, 1917.

Parseval [PL13] Airship

Designed by German Army Major August von Parseval, this was a world-famous type of airship with a non-rigid structure. In 1911, the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group had sent Army engineer Shūhei Iwamoto to Germany, where he purchased a Parseval PL13 for 230,000 yen. Arriving in Japan in August 1912, the airship was assembled in a hangar at Tokorozawa, completed on the last day of that month and made the first visit of an airship to Tokyo on October 21 that year. Playing an important role in training and public demonstration flights, she suffered extensive damage when participating at such an event at the Aoyama Army Parade Ground [on March 28, 1913, an event overshadowed by that day’s Blériot crash, which claimed the lives of pilots Kimura and Tokuda]. Her service career having prematurely ended after seven short months, she was resurrected as the Yūhi-Gō and enjoyed a new lease of life for four more years.

Astra-Torres AT-2 Airship

This non-rigid airship was purchased from the French Nieuport-Astra company by the Imperial Japanese Navy. Assembled in what had been the Yūhi-Gō’s hangar at Tokorozawa, she was completed on July 10, 1923. Her drawbacks were that, as a non-rigid airship, she was too big and unwieldy, her handling presented difficulties and maintenance was costly. As an airship hangar [received as war reparations from Germany after World War I] had been completed at the Navy’s Kasumigaura airfield in Ibaraki Prefecture, she was moved there from Tokorozawa on December 15 that same year.

I-Gō Airship

Designed by the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group, the I-Gō was Japan’s first military airship. Completed at Tokorozawa in August 1911, she made her first flight from here on October 24 that year. Four days later, she completed the first long-distance flight by a military airship, centred on but venturing outside the perimeter of Tokorozawa airfield and covering 33 km in 1 hour and 40 minutes.

The top two photos on the right-hand panel are of the Yūhi and its gondola, those below are of the AT-2 and its gondola. The latter was 16.2 metres long, 1.7 metres wide and 2.0 metres high.

(Photo: November 2019)

(Photo: November 2019)

|

[Panel 5/7, (left, not shown)] 第一世界大戦と所沢 The Tokorozawa Airfield during World War I |

||

| In World War I, which broke out on July 28, 1914, Japan sided with the Allies and declared war against Germany. To attack the German forces that had occupied Tsingtao, in Shandong province on the Chinese mainland, the Imperial Japanese Army formed a Provisional Air Squadron at Tokorozawa airfield the following month, on August 17. Sent to China, the unit’s aircraft and crews participated in attacks from the end of September 1914 and, in the period up to the fall of Tsingtao on November 7, acquitted themselves well on reconnaissance and bombing missions. This marked the debut of Japanese Army aircraft in in actual combat. |

||

The central panel depicts (from top) a Nieuport NG monoplane, a tethered balloon and a 1913 Model Maurice Farman. The top right photo shows a Maurice Farman aircraft in action at Tsingtao, the photo below it the tubes used to drop bombs.

The caption gives some more information about the Tsingtao operation. The Provisional Air Squadron was a composite unit comprising four 1913 Model Maurice Farman biplanes, a Nieuport NG monoplane and tethered balloons. During a total of 86 sorties, the unit conducted 15 air raids during which 44 bombs were dropped.

Two of the four Maurice Farman aircraft operated from the Imperial Japanese Navy seaplane

Two of the four Maurice Farman aircraft operated from the Imperial Japanese Navy seaplane

carrier Wakamiya seen at Shazikou, east of Tsingtao, China, in October 1914. Having

launched the world’s first air raid mounted by ship-borne aircraft on September 5,

1914, the Wakamiya had struck a German mine on September 30. Thus the

aircraft were shore-based while the ship underwent repairs.

(Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Air raid methods were primitive and involved the rear-seat crew member dropping the bombs down circular tubes made of tin plate attached to the left side of his seat. At first, they had dropped shells with parachutes attached, but when these hit the ground they had a tendency to fall sideways and fail to explode. Thus arrow feathers were attached instead, so that the shells would hit the target vertically. Also, as there were then no aircraft equipped with armament, the rear-seat crew member would fire a hand-held light machine gun.

Taken on January 1, 1915, the photo on the bottom right of the panel depicts a scene from the Provisional Air Squadron’s triumphal return from the China front line. As the squadron member’s made their way from Tokorozawa Station to the airfield, they were cheered on by the local populace, who had built a victory gate to mark the occasion. The sign above the gate says ‘in celebration of a triumphal return’.

(Photo: May 2013)

(Photo: May 2013)

|

[Panel 6/7] 所沢飛行場と教育活動 Education at the Tokorozawa Airfield |

||