Japanese Aviation History (to 1945)

There are already several sites “out there” that are dedicated to mining the rich vein that is Japanese aviation history up to 1945. More information on the selected content of this section will be released nearer the time.

As a taster, there was no better place in Japan to start than where it all started more than a century ago, Yoyogi Park: Takeoff Point for Japanese Powered Flight (link).

For the second feature, J-HangarSpace brought its searchlight to bear on a little-known organization that is dedicated to preserving as much as possible that remains of the wealth of Japanese aviation history from that period. The account then goes on to provide details of the aircraft and one location (in that same Yoyogi Park) that have received official certification under an Important Aviation Heritage Asset programme.

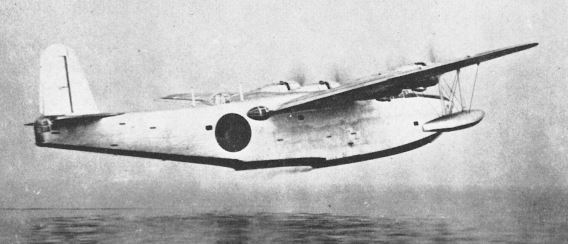

The next topic on this page was prompted by writing the review of a book devoted to the Kawanishi Type 2 Flying Boat (Emily), Bunrindo’s Famous Airplanes of the World No. 184 (link). Overstepping the ‘up to 1945’ limit, J-HangarSpace has compiled an illustrated chronology of the events that have occurred to the one remaining example in the nearly 80 years that have now passed since it was built in 1943. The chronology is followed by a selection of other photographs, including of the Seikū (Clear Sky) transport version.

The latest addition arose from a chance, stoney-faced encounter in Hiroshima . . .

(All photographs on this website are copyright J-HangarSpace

unless otherwise stated.)

Young Pioneers: Toyotarō Yamagata and

Other Key Figures from Early Days of Japanese Aviation

During a September 2022 visit to Hiroshima, J-HangarSpace was surprised to come across a statue of a pilot, goggles in hand and wearing an old-style flying suit, in the precincts of a shrine close to the main train station. The statue is of Toyotarō Yamagata (1898–1920) and its location the aptly named Tsuruhane (Crane Wings) Shrine, its new name chosen in 1872 as nearby Mt. Futaba was thought to bear a resemblance to a crane with outspread wings.

Toyotarō Yamagata

Toyotarō Yamagata

(Photo [posted April 2020]: 吉塚康一 via Twitter @KoichiYoshizuka)

Born the third son of one Momotarō Yamagata in Hiroshima’s Kyobashicho district on September 23, 1898, Yamagata had apparently become obsessed with aircraft in 1912, when he was taken up for a flight from the city’s military parade ground in the Narahara No. 4 Otori by aviation pioneer Einosuke Shirato (1885–1936). Yamagata himself came from what was, as far as can be said for the time, a family with aviation connections. His uncle was Shigesaburō Torigai*, who can be seen here (link) in front of his Otemachi, Tokyo, auto repair shop in 1902; the car is an Oldsmobile purchased in the capital’s Ginza district. With the help of others in the then small-radius aviation circles, Torigai subsequently completed an aircraft he called the Hayabusa (Peregrine Falcon). Despite apparently never having received any formal flight training, he piloted the aircraft himself and crashed twice, in May and September 1913. Torigai had acquired his aircraft’s imported French Grégoire Gyp aeroengine from an aircraft that had inauspiciously crashed earlier that year.

Having moved to Tokyo to live with his undaunted uncle in 1914, the following year the 17-year-old Yamagata was one of the first students to enter the Itō Aircraft Research Institute, which had been founded by another aviation pioneer, Otojirō Itō (1891–1971), in Inage, Chiba Prefecture. Sited on the shore of Tokyo Bay, the mudflats there were seen as a potential low-cost, low-tide (but hence strictly limited-operation) airfield; an archive photo from 1915 shows Yamagata and one Seitarō Tamai (born 1892) standing amongst the muddy puddles next to the decidedly spindly-looking Modified Hayabusa, at the controls of which sits its then owner/redesigner Itō.

Despite his tender years, after having graduated top of that first intake in 1917, Yamagata assisted on the project that he bestowed with the name shared by his family’s ancestral shrine and a deceased sister** and culminated in the Tsuruhane 1 trainer aircraft, which was completed and test flown by Itō on May 8, 1918. Through the good offices of Yamagata’s uncle, its French 50hp Gnome rotary engine had been sourced from another aircraft that had been involved in, in this case, a fatal accident. The Tamai No. 3 had crashed due to wing strut failure on takeoff from Shibaura, Tokyo, on May 20, 1917. Happening at the start of a third flight on which military pilot recruitment leaflets were to be dropped over the capital, the accident had claimed the lives of the aircraft’s builder and Nippon Flying School instructor, that same Seitarō Tamai***, and a newspaper photographer.

Visiting U.S. Pilot Influencers

In the 1910s, the main activity of the fledgling civil aviation industry was to hold touring flying circuses for which an admission fee was charged. These traveled around the country with an aircraft, be it domestically built or imported, to demonstrate to local populaces what aircraft were and what they could do.

The model for these flying circuses had been provided by the Baldwin troupe of performing aviators. Pioneer U.S. balloonist Thomas Scott Baldwin (1854–1923), who had once worked as an acrobat in a traditional circus, had brought two of his self-designed, Glenn Curtiss-built biplanes (named Red Devil and Skylark) to Japan in March 1911—as seen in this postcard in the Japan Archives (link)—at the tail-end of an Asian tour. Assisting him in demonstrating a very early form of barnstorming in this still new-fangled invention, Baldwin was accompanied on the tour by aviators James C. “Bud” Mars (1875–1944 [link]) and Theodore “Tod” Shriver (1873–1911 [link]).

The April 3, 1911, edition the Asahi Shimbun reported that an astounding 400,000 spectators had flocked to see Baldwin’s flying circus perform free public flights at the Joto military parade ground in Osaka, an event that has been described as Japan’s first air show.

Baldwin’s team had gone on to wow the crowds with the first demonstrations of aerobatics at locations that included four days of flying at the horse racing track then located in Meguro, Tokyo. The same newspaper article included a photo from there, showing some of the 2,000 invited elementary school students in the stands, looking up in wonder at a flying machine. On one occasion, pilot Mars had not only performed aerobatics but also dropped a mandarin orange “bomb” on the National Diet Library building from around 300 feet.

On April 29, 1911, a new project involving racing against cars was launched at the Sayonara Air Meet at Kawasaki race course, Kanagawa Prefecture. The Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun reported that on the last day (May 2), the Mars-piloted Red Devil was roundly beaten by 12 seconds over the two-mile course by equally fervent car advocate Kishichirō (later Baron) Okura (1882–1963) driving a Fiat sports car.

Around the time when Yamagata would have been receiving basic training, Charles Niles (1888–1916), who came to Japan in December 1915—to be followed by Art Smith (1890–1926) in 1916 and 197 and Katherine Stinson (1891–1977) from December 1916 to May 1917 and again in September 1917—was touring Japan to likewise demonstrate how he could put an aircraft through its paces. These flights likewise featured aerobatics, such as loop-the-loops and spins.

External influences 1. (Above) Thomas Scott Baldwin in the early 1910s;

External influences 1. (Above) Thomas Scott Baldwin in the early 1910s;

Art Smith in Chicago in March 1915

(Photos: [Top] via Wikimedia Commons;

(Photos: [Top] via Wikimedia Commons;

[above] Chicago Daily News Collection/Chicago History Museum via Wikimedia Commons)

External influences 2. Before the days of signs saying “No smoking within 50 feet,”

External influences 2. Before the days of signs saying “No smoking within 50 feet,”

Charles Niles in 1913; a kimono-clad Katherine Stinson standing in front of

her aerobatic, Gnome-powered Partridge-Keller aircraft, Tokyo, 1916.

(Photos: [Top] Bernard Smith Collection/U.S. Marine Corps Archives via Wikimedia Commons;

(Photos: [Top] Bernard Smith Collection/U.S. Marine Corps Archives via Wikimedia Commons;

[above] George Grantham Bain Collection/U.S. Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons)

Under such circumstances, there were many people in the fledgling Japanese civil aviation industry, including the young, up-and-coming aviator Yamagata, who fervently aspired to perform aerobatics.

New Beginnings, Design Changes Instituted

In between times, following a storm surge that had devastated Inage in September 1917, a suitable new Chiba Prefecture home for the Itō Aircraft Research Institute had been found in Saginuma (literally Heron Marsh), Tsudanuma, in what is now part of the city of Narashino, where work recommenced in 1918.

Following his graduation from the Itō institute, Yamagata had been awarded Japanese pilot’s licence No. 11. Commencing with flights around Hiroshima, he attracted the attention of The Asahi Shimbun newspaper company, which resulted in a 1918 tour of Korea, which had formed part of the Japanese empire since its annexation in 1910. In the spring of 1919, he gave a series of exhibition flights in Osaka.

He went on to enter the record books as the first Japanese civilian pilot to emulate his U.S. influencers by performing two consecutive loop-the-loops in the Tsuruhane 2 on May 4, 1919.

Yamagata obviously having had no experience of looping the loop, it was Itō Aircraft’s chief engineer Tomotari Inagaki who had somehow managed to track down a book about piloting aircraft that had been published in Britain. Inagaki had explained its content on aerobatic manouevres to Yamagata, who had been tying himself in an upside-down position to get used to the sensation for inverted flight.

Key Team Member Inagaki

Little is known about Inagaki, who had joined the institute’s design team in October 1918 while still enrolled at what is today the Tokyo Institute of Technology and became its chief engineer after graduation. From January 1919, he worked on his first project, using the Tsuruhane 1’s already previously used engine for the development of the Tsuruhane 2. From the outset, Inagaki designed the Tsuruhane 2 to be Japan’s first aerobatic aircraft, at a time when neither the Army nor the Navy possessed an aircraft specifically designed or even cleared for aerobatics. The Tsuruhane 2 was completed on April 21, 1919, and Yamagata himself had participated in the aircraft’s test flight programme from April 24 that immediately preceded his record-breaking manoeuvre on May 4.

Successes Brought to Untimely End

Six days after his looping-the-loop feat, on May 10, 1919, Yamagata participated in the Imperial (now Japan) Aeronautic Association’s contribution to festivities marking 50 years since Japan had moved its capital from Kyoto to Tokyo. Once again at the controls of the Tsuruhane 2, which carried a white crane marking on both sides of its fuselage, Yamagata had taken off in windy conditions from Susaki airfield in the capital’s Koto Ward and performed two loops in a row over Ueno. For this feat, Yamagata was acclaimed by many of the evening newspapers on that day, and suddenly became the leading figure in aerobatics.

Flying the Itō-designed Emi No. 14, he went on to claim the 10,000-yen prize for winning the Imperial Aeronautic Association’s non-stop Tokyo-Osaka-Tokyo air race on April 21, 1920, completing the 840-km course in a then new record time of 6 hours 43 minutes.

Tragedy was to befall the 22-year-old pilot just four months later. On August 29, 1920, Yamagata was attempting three consecutive loop-the-loops over Saginuma when the upper wing of the very same Emi No. 14 suffered structural failure and he lost his life in the resulting crash, when the aircraft span into the ground in a field. (Charles Niles had been killed in the same circumstances in what was to become a town synonymous with aviation, Oshkosh, Wisconsin, in June 1916.)

It must have come as an immeasurable shock to Itō, as Yamagata had been his right-hand man since the founding of his institute. Such was his high media profile that news of his death prompted the newspapers of the time to publish extra editions. In his memory, Itō produced the Inagaki-designed Itō Emi No. 22 Yamagata Kinen-go (Yamagata Commemorative) aircraft, which was completed in the spring of 1922 and is seen here at Tsudanuma (link).

Hundreds of people attended Yamagata’s ceremony at the funeral hall in Aoyama, Tokyo. The Civil Aviation Bureau paid special condolence money amounting to 5,000 yen to the bereaved family and, to promote aviation, 7,000 yen to the Itō institute for the aircraft in which Yamagata had lost his life.

Meanwhile, over in Hiroshima . . .

In Yamagata’s home city, there were around 3,000 mourners present for the main funeral ceremony at the Jisenji Temple, to which a propeller from an Itō Emi aircraft was handed over for preservation; another propeller, of unknown provenance, was donated to Hiroshima Municipal Danbara Elementary School, which Yamagata had presumably attended. (After having been purchased from Itō’s flying school by a private owner, the Tsuruhane 1 was eventually donated to the Itsukushima Shrine on Miyajima, Hiroshima.)

The Tsuruhane Shrine had been given its name by the lord of the Hiroshima domain in 1868, the first year of the Meiji era. At that time, cranes were a frequent sight in Hiroshima, which has resulted in local place names having the prefix tsurumi (crane sighting) to this day. The shrine houses the guardian deity of the Yamagata family.

Cast by a local sculptor and given pride of place there in 1921, the year after its subject’s untimely demise, the original bronze statue of its famous pilot son in a flying suit was removed when the Metal Recovery Act for the war effort came into effect in 1944. In the intervening 57 years, a dilapidated pedestal was all that remained before the current imposing, full-size stone statue was eventually erected, thanks to the efforts of local volunteers, in August 2001.

. . . and in Chiba Prefecture

(Photo [posted April 2020]: 吉塚康一 via Twitter @KoichiYoshizuka)

(Photo [posted April 2020]: 吉塚康一 via Twitter @KoichiYoshizuka)

Itō made the arrangements for a stone pillar monument to be erected near the crash site and dedicated on August 29, 1940, 20 years to the day after Yamagata’s death. The vertical text was written by Sanji Narahara, designer of the Otori, the aircraft in which the young Yamagata had taken his first air experience flight. (Four years before, in 1936, Itō had also lost his eldest son Shintarō in an air crash.)

About two metres high, the monument is located in the middle of a field on a hill in Tsudanuma, a 10-minute walk from either of the Makuharihongo train stations. Narcissuses have been planted in front of the monument, which has been cared for by the local people, and the Tsudanuma municipal authorities early imposed building restrictions on the adjacent land. Photographs from March 2021 show the pillar itself as being still in good condition, but the dedication plaque, not surprisingly, badly weathered.

Having spent his youth in Saginuma, Itō settled in Narita after the war and managed some pastureland only to be one of those evicted, aged 77, to in his case ironically make way for the construction of the airport in 1963. He had then returned to Saginuma, and was thus living locally in 1969 when he attended a ceremony in front of the monument to mark the 50th anniversary with Naoji Yamagata, the late pilot’s younger brother, whose name appears as one of four donors on the stone statue’s pedestal. As of late 2019, Itō’s youngest daughter was still tending the memorial and leaving notes requesting that visitors kindly respect Yamagata’s memory by not leaving litter at the memorial.

The nearby Sodegaura No. 2 Municipal Children’s Playground features a large display panel (link), erected by the Narashino City Council’s Board of Education in March 2006, recalling the reclaimed land location’s time as the site of the former Itō Aircraft Research Institute’s runway. The display panel reads:

The Itō Aircraft Research Institute was opened by Otojirō Itō along the former Chibagaidō [the Edo period highway that ran from Tokyo’s Edogawa Ward to Chiba] in Saginuma 3-Chōme on April 1, 1918.

An apprentice of [Sanji later] Baron Narahara, who had opened Japan’s first civilian flight training school in 1912, Itō had gone his own way and established the Itō Aircraft Research Institute on the Inage seashore in 1915. However, as those facilities were devastated by a typhoon and tidal surge in September 1917, he restarted operations from the Saginuma seashore the following year. At that time, this area had a shallow sea, and after the tide went out, the tidal flats formed a suitable runway, from which about 150 pilots were trained.

In 1931, the institute was divided into aircraft building and pilot training departments, which comprised the Itō Aircraft Manufacturing Works and the Toa and Teikoku flying schools. Following the end of the Pacific War in August 1945, all ceased to exist. In the 30 years since its founding in 1915, the Itō operation had built 54 aircraft and more than 200 of 15 types of glider.

The first of the great archive photos on this page (link) of the Japan Aeronautic Association website shows (from left to right) Otojirō Itō, Toyotarō Yamagata, and Tomotari Inagaki standing in front of the Tsuruhane 2 at the Itō Aircraft Research Institute on April 28, 1919. The fourth and last photo, at the foot of the page, shows those present at the institute for the graduation ceremony of the first pilot course on November 29, 1921, after the Spanish flu outbreak (the COVID-19 pandemic of the time) had subsided. Itō is third from the left on the front row, and Inagaki on the right of the back row. Also of note, on the extreme left of the front row, is Tadashi Hyōdō (1899–1980), the first Japanese woman to gain a pilot’s licence.

* Sometimes appears in references as Torikai, but written as Torigai in a Japan Aeronautic Association source.

** It was in his series of postwar evening newspaper articles, which recorded the prewar popular culture history of Hiroshima, that the first announcer at the NHK (Japanese BBC) Hiroshima radio station and local historian Tarō Susukida (1902–1967) stated that the aircraft had been named after a deceased sister.

*** Returning to their hometown of Yokkaichi, Mie Prefecture, by two years Tamai’s younger brother Tōichirō had eventually mounted a flight in tribute to his late brother; after having experienced and survived two crashes, he succeeded only at the third attempt. Fortunately, he was able to take over the baton from his brother and enjoy a long and successful career in aviation advertising and training from Tokyo’s Haneda Airport, passing away from natural causes at the age of 83 in 1978.

Parting Shots

(Tsuruhane Shrine, Hiroshima, September 2022)

(Tsuruhane Shrine, Hiroshima, September 2022)

*****************************************

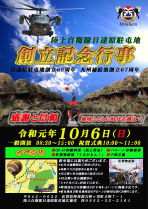

The red carpets are rolled out ahead of the official ceremony marking the arrival of the sole surviving

The red carpets are rolled out ahead of the official ceremony marking the arrival of the sole surviving

Emily at its current resting place, JMSDF Kanoya, in April 2004. (Photo: JMSDF Kanoya)

From Konan to Kanoya: The Wanderings and Wallowings of Emily c/n 426

| Mar. 1943 | Built as Type 2 Model 12 (H8K2) at Kawanishi’s Konan Plant, Hyogo Prefecture, handed over directly to 802nd Kōkūtai (Naval Air Group) as ‘N1-26’ (FAoW No. 184 includes profile) |

| 1943 | Serves with 802nd, then operating primarily from Jaluit Atoll (Marshall Islands), and Makin in Gilbert Islands (now part of Kiribati) |

| Sept. 1943 | 802nd tail code changed to Y4 (aircraft’s to Y4-26?) |

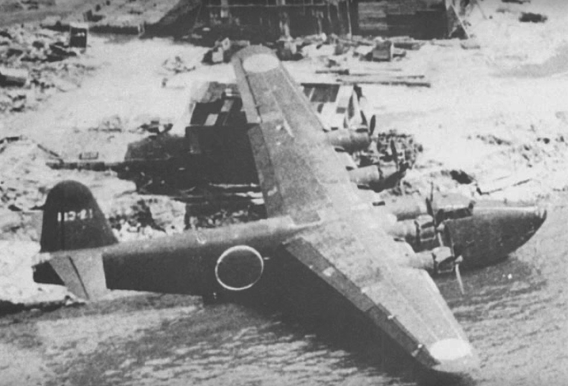

(Above and below) Emily c/n 426 was lucky to avoid suffering a similar fate to this sister aircraft,

(Above and below) Emily c/n 426 was lucky to avoid suffering a similar fate to this sister aircraft,

destroyed during the U.S. invasion of Makin in November 1943.

(Photos: [above] via YouTube [link]; [below] National Archives and Records

Administration via Wikimedia Commons)

| Jan. 1944 | (29th) 802nd relocates to Saipan in the Marianas, aircraft possibly one of those temporarily deployed to Truk (now Chuuk, Micronesia) |

| Apr. 1944 | (1st) Passed to 801st Kōkūtai on Saipan as ‘801-86’ |

| July 1944 | (10th) 801st Kōkūtai returns to Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture |

| Jan. 1945 | (1st) 801st becomes part of Maritime Escort General Headquarters |

| Feb. 1945 | (11th) Upon 801st’s disbandment, aircraft passed to Japan-based 5th Naval Air Wing, becomes Takuma Air Group ‘T-31’ at Takuma, Kagawa Prefecture (part of same unit’s Kikusui [Floating Chrysanthemum] Force from Apr. 25, 1945) until disbandment on Aug. 22, 1945 |

| Oct. 1945 | Having survived the war with only minor damage, aircraft also lucky to be selected for evaluation from three aircraft found at Takuma; other two destroyed on site |

| Nov. 1945 | (11th, possibly 13th) Having been repaired by former IJNAF maintenance team from Kure, Hiroshima Prefecture, flown for last time in Japan from Takuma back to Yokohama by war veteran crew for transshipment to United States |

| Dec. 1945 | (10th) Now bearing U.S. national markings, loaded aboard U.S. Navy transport vessel for voyage across Pacific |

| Jan. 1946 | Offloaded for initial evaluation at Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, Washington |

The aircraft sports U.S. markings for her initial evaluation at NAS Whidbey Island in Washingtom

The aircraft sports U.S. markings for her initial evaluation at NAS Whidbey Island in Washingtom

state in 1946. The span of the outer wing alone was roughly equivalent to that of a Zero fighter.

(Photo: via YouTube [link])

| Feb. 1946 | Having been transferred to another vessel for passage through Panama Canal, arrives in Norfolk, Virginia, for reassembly |

| May 1946 | (23rd) Makes what is to prove to be sole flight in United States when ferried from NAS Norfolk to test centre at Patuxent River, Maryland |

| Aug. 1946 | (22nd) Taxy tests on Patuxent River start |

| Jan. 1947 | (30th) Test programme in United States ceases due to engine failure after 12.6 hours of operations |

(Above and below) Two views of the aircraft during evaluation at the Patuxent River test centre. That

(Above and below) Two views of the aircraft during evaluation at the Patuxent River test centre. That

above is one of a series of photos taken during the evaluation of spray patterns. This image shows

that generated when the aircraft weighed 49,900 pounds (22,630kg) and was taxied at 20 knots.

(Photos: [above] U.S. Navy via Wikimedia Commons; [below] from Apr.1952 issue of

The World’s Aircraft, used with permission of Hobun Shorin, Co., Ltd.)

| Feb. 1947 | Transported back to Norfolk by road and placed in open-air storage |

| 1949 | Decision made to remove wings and formally preserve aircraft in rubber protective coating |

The aircraft surrounded by a scaffold to facilitate mothballing at NAS Norfolk in 1949.

The aircraft surrounded by a scaffold to facilitate mothballing at NAS Norfolk in 1949.

(Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

| Late 1959 | (Reported in Feb. 1960 issue of Aireview) Aircraft’s lead designer and then Shin Meiwa company advisor Dr. Shizuo Kikuhara (1906–1991) travels to NAS Norfolk at U.S. Navy’s invitation, agreement in principle reached on aircraft’s return |

| Sept. 1960 | Starboard outer engine sheared off when aircraft blown over in Hurricane Donna |

| June 1978 | U.S. Department of Defense plans to scrap aircraft to save money come to attention of well-connected former politician and influential business figure as well as first Museum of Maritime Science curator Ryōichi Sasakawa, who is instrumental in arranging repatriation and preservation procedures |

A photo of Ryōichi Sasakawa (1899–1995) on the cover of a biography published in 1978,

A photo of Ryōichi Sasakawa (1899–1995) on the cover of a biography published in 1978,

the title of which describes him as being unprecedented (or unconventional). That an

example of an Emily still exists is in no small part due to the efforts of this one-time

controversial political and business figure, who went on to receive wide acclaim for

the charitable contributions of the Nippon Foundation he had launched in 1962 (link).

| Oct. 1978 | U.S. House of Representatives officially decides to make aircraft first spoils of war item to be returned to Japan |

| Apr. 1979 | Type 2 Flying Boat Repatriation Executive Committee formed |

| Apr. 1979 | (23rd) Attended by Sasakawa, ceremony held at NAS Norfolk to mark return to Japanese ownership. (Aircraft still lacks starboard outer engine) |

| May 1979 | Disassembled and cocooned for transshipment at NAS Norfolk |

| June 1979 | (19th) Loaded aboard container ship New Jersey Maru |

| July 1979 | (13th) Arrives at Port of Tokyo, transferred by floating crane to Museum of Maritime Science, ‘lands’ back on Japanese soil for first time in 35 years |

| Feb. 1980 | Restoration work begins |

| June 1980 | (3rd) Lifted by crane into display position |

June 3, 1980. Mounted on the back of a trailer minus its outer engines and wing sections, the Type 2

June 3, 1980. Mounted on the back of a trailer minus its outer engines and wing sections, the Type 2

Flying Boat is slowly maneuvered into position at what will be its home for the next 24 years.

(Photo courtesy of Museum of Maritime Science, Tokyo [link])

| July 1980 | (14th) Restoration work completed (link) |

| July 1980 | (15th) Aircraft’s interior shown to press |

| July 1980 | (20th) Tape-cutting ceremony held on first day on public display at Museum of Maritime Science. Event attended by former Lt. Cdr. Tsuneo Hitsuji (1914–1995), who as last CO of Takuma Air Group had piloted aircraft on ferry flight to Yokohama in Nov. 1945 |

One of the scenes of celebration on July 20, 1980, to mark the first day the aircraft was officially open

One of the scenes of celebration on July 20, 1980, to mark the first day the aircraft was officially open

to public view in its original, post-restoration state.

(Photo courtesy of Museum of Maritime Science, Tokyo)

| Jan. 21–Mar. 26, 1982 | Surrounded by scaffolding for long-term preservation work, including application of special paint (see photo below) |

| Mar. 27, 1982 | Ceremony marking completion of long-term preservation work conducted by Shinto priest |

The aircraft is pictured here during the process of applying two coats of a green polyurethane aircraft

The aircraft is pictured here during the process of applying two coats of a green polyurethane aircraft

coating, which was an exact match for the former IJNAF dark green, to her upper surfaces and the

sides of the boat hull, February 27, 1982. (Photo courtesy of Museum of Maritime Science, Tokyo)

(Above and below) Fast forward to July 1998 and two more views of the Emily at the Museum of

(Above and below) Fast forward to July 1998 and two more views of the Emily at the Museum of

Maritime Science, already 16 years after the first application of the special protective paint.

Mention should also be made of the long-term preservation efforts, which included controlling the

Mention should also be made of the long-term preservation efforts, which included controlling the

temperature of the interior, conducted during the 34 years the Emily was U.S. government property.

| Events of 2004 | |

| Dec. 2003 | Aircraft’s management transferred from Museum of Maritime Science to then Japan Defense Agency (now Ministry of Defense), decision made to move aircraft to Kanoya |

| Feb. 2 | Dismantling works starts |

| Mar. 3 | Loaded aboard cargo vessel at Tokyo |

| Mar. 7 | Offloaded at Port of Kagoshima |

| Mar. 8 | Early in morning, arrives by road at JMSDF Kanoya |

| Apr.26 | On outdoor display at JMSDF Museum |

Primary Reference Sources:

Ni-shiki Hikōtei (Type 2 Flying Boat), Famous Airplanes of the World No. 184 (Bunrindo [Japan], March 2018)

H8K Emily Type 2 Flying Boat, Aero Detail No. 31 (DaiNippon Kaiga [Japan], 2003)

Ni-shiki Ōgata Hikōtei (Type 2 Large Flying Boat), Museum of Maritime Science Guide 2, 2002

Ni-shiki Ōgata Hikōtei (Type 2 Large Flying Boat), Museum of Maritime Science Guide 2, 2002

Ni-shiki Hikōtei (Type 2 Flying Boat), Famous Airplanes of the World No. 49 (Bunrindo [Japan], November 1994)

http://arawasi-wildeagles.blogspot.jp/2017/01/kawanishi-h8k-pt1.html

https://www.pacificwrecks.com/aircraft/h8k/426.html

http://dansa.minim.ne.jp/CL-NisikiDaitei-1.htm

Kanoya, January 2014. Although tethered down, there must be some concern that the aircraft, which

Kanoya, January 2014. Although tethered down, there must be some concern that the aircraft, which

suffered hurricane damage in 1960, will fall victim to one of Japan’s many typhoons.

(Photo: Miya.m via Wikimedia Commons)

The aircraft’s weight is also well supported on struts. Visible just behind the main front underside strut is

The aircraft’s weight is also well supported on struts. Visible just behind the main front underside strut is

the bomb aimer’s window, which in the case of this aircraft reportedly saw very little use. The white boxes

above the undercarriage dollies are floats, used in conjunction with fishing net-type flotation devices to

retrieve each 1,850lb (840kg) twin-wheel dolly when jettisoned prior to takeoff.

(Photo: Miya.m via Wikimedia Commons [Jan. 2014])

(Above and below) The first prototype of what was then known as the 13-Shi Large Flying Boat first flew

(Above and below) The first prototype of what was then known as the 13-Shi Large Flying Boat first flew

on December 31, 1940, and is shown here during flight tests on Osaka Bay from Kawanishi’s Konan Plant

the following month. In the meantime, the top of the aircraft’s tail had undergone modification, as had the

boat hull beneath the nose by the addition of a so-called katsuobushi (piece of dried bonito) strake to

to reduce the spray that had caused problems during the takeoff run for its maiden flight. A total of

17 H8K1 aircraft had been built at Kawanishi’s Naruo Plant by 1943, when production switched to the

H8K2 version at the Konan Plant. The World’s Aircraft for June 1953 claims an astounding 111 aircraft

were built there in 1943, followed by 67 in 1944 and just two in 1945, for a total of 180 aircraft.

(Photos from June 1953 issue of The World’s Aircraft, used with permission of Hobun Shorin, Co., Ltd.)

Pictured at Kawanishi’s Naruo Plant on November 30, 1943, directly after completion, is the 68th Type 2

Pictured at Kawanishi’s Naruo Plant on November 30, 1943, directly after completion, is the 68th Type 2

Model 12 Flying Boat converted as the first production example of what was then provisionally

designated as the Seikū (Clear Sky) Model 32. The propeller blades were unpainted and the

aircraft sported red ‘identification friend or foe’ stripes on the leading edges of its wings.

A total of 15 aircraft of this version were completed.

(Photo from June 1953 issue of The World’s Aircraft, used with permission of Hobun Shorin, Co., Ltd.)

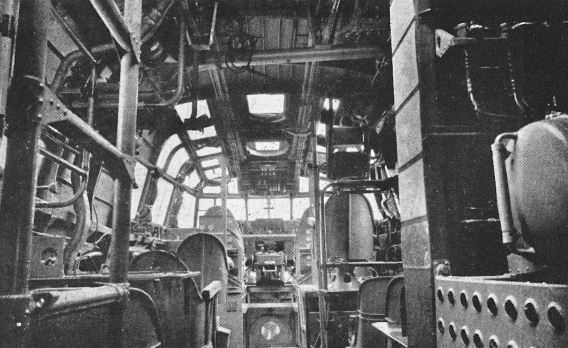

The view forward to the aircraft commander’s seat and flight deck from the radio operator’s position

The view forward to the aircraft commander’s seat and flight deck from the radio operator’s position

on the first Seikū transport aircraft.

(Photo from June 1953 issue of The World’s Aircraft, used with permission of Hobun Shorin, Co., Ltd.)

The Seikū transport aircraft could accommodate a maximum of 64 passengers in a troop-style seating

The Seikū transport aircraft could accommodate a maximum of 64 passengers in a troop-style seating

arrangement on two decks. Depicting the first aircraft specially prepared for a photo shoot,

its operational appearance was likely somewhat different.

(Photo from June 1953 issue of The World’s Aircraft, used with permission of Hobun Shorin, Co., Ltd.)

Nicknamed Asahi (旭), this is another of the Yokohama Naval Station-based Seikū Model 32

Nicknamed Asahi (旭), this is another of the Yokohama Naval Station-based Seikū Model 32

transports mentioned in the review of the Famous Planes of the World book on the Emily (link).

The book (p. 49) contains the scene, soon after the war’s end, of six aircraft congregated on the

ramp at Negishi, where this photo was taken. Of note is the aforementioned katsuobushi strake

under the nose, the design fix first added to the 13-Shi prototype to reduce spray and alleviate

the aircraft’s tendency to porpoise on takeoff runs.

(Photo from Nov. 1956 issue of The World’s Aircraft, used with permission of Hobun Shorin, Co., Ltd.)

A lone Emily sits forlornly on the shore having seemingly run aground at the now wrecked Hiro Naval

A lone Emily sits forlornly on the shore having seemingly run aground at the now wrecked Hiro Naval

Arsenal in Hiroshima Prefecture, where some of the type’s smaller predecessors had been developed

during the interwar years. The remains of the facility’s slipway are in the right background.

(Below) A close-up of the above photo, which was likely taken soon after the end of the war, reveals the

aircraft to be a Seikū Model 32 transport bearing the tail code 11Ko-21, 11Ko having been that assigned

to the 11th Naval Arsenal at Hiro. Hiroshi Ebi’s caption for this photo in FAoW No. 184 states that the

patch at the rear centre of the main wing covers a hole made to facilitate the replacement of a fuel tank.

Easy targets, more than half the total of 36 Seikū transports built fell victim to marauding U.S. fighters.

(Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum via Wikimedia Commons)

Pause for Thought

Test your recognition of Japanese World War II aircraft undercarriage legs with this quiz, found in the second (July 1952) issue of The World’s Aircraft and reproduced here with the kind permission of Hobun Shorin, Co., Ltd. Answers at (where else?) the foot of this page.

Japan Aeronautic Association Aviation Heritage Archive

Domestically, Japan maintains a tradition of preserving and registering cultural properties. Over the years, the main targets for preservation have been treasures and buildings owned, for example, by shrines and temples as well as museums. Internationally, the country has been pushing to add to its total of 20 UNESCO World Heritage sites inscribed under the convention since joining in 1992.

Few outside Japan will be aware that this preserving and registering of tangible assets extends to the world of aviation. Established in 2004 as part of the Japan Aeronautic Association (JAA), the three-man team at the Aviation Heritage Archive, which operates from a small office in its parent organization’s headquarters building in Tokyo, is tasked with researching, collecting, preserving and making publicly available Japanese aviation artefacts.

(Japan Aeronautic Association Aviation Heritage Archive)

(Japan Aeronautic Association Aviation Heritage Archive)

Private individuals and families involved in earlier eras that produced breakthroughs in aviation have been preserving documents that recognize the importance of those eras, but the numbers of both custodians and documents are slowly declining with every passing year. Many valuable documents will already have been discarded as they were deemed of little value. Since its inception, the Archive thus sees itself involved in a race against time to preserve for posterity any of the remaining artefacts and documents before they vanish, items that may have been handed down but become scattered and possibly damaged in the process.

The Archive sees its remit as helping to show that the development of aviation in Japan was not achieved simply and solely in imitation of advances made in the United States and Europe. The feeling is that Japan’s aviation development was rooted in the traditions of monozukuri (manufacturing or craftsmanship) that date back to the Edo period (1603–1868) and can best be understood by properly collecting and collating as well as verifying documentation from the dawn of aviation in the 20th century.

Regarding documents as no less important than the aircraft themselves, the items that the Archive is charged with conserving range from blueprints and photographs to aircraft components and complete aircraft. Also highly prized and sought after are the accounts of people who experienced or were present at aviation-related events and who thus offer the unique vantage point of having been eyewitnesses to history.

Among the recent (March 2017) additions were two engine manuals that were used by 2nd Lt. Nobuo Ishimoto, who was born in 1919 and at the end of the war in 1945 primarily responsible for maintaining the carburetors of Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF) fighters at Fussa airfield, Tokyo. Donated by Ishimoto’s son, one manual from November 1942 covers the parts and assembly inspection procedures for the Ha-40 engine. Produced by the Kawasaki engine plant in Akashi, Hyogo Prefecture, in September 1944, the other manual describes the methods for handling the Ha-60 Model 41 (or Ha-140 under the unified Army/Navy designation system). Both of these powerplants were fitted to versions of the Kawasaki Ki-61 (Type 3) Hien fighter.

Having focused on activities geared toward the preservation of photos and paper documents, in both original and digitized forms, the Archive has in place an Aviation Heritage Inheritance Fund to support its aims and encourage holders of important items to make them available for the national good.

Under a certification system set up in 2007, the Archive has awarded nine Important Aviation Heritage Asset certifications since 2008, seven of which are of relevance to the subjects covered by this website. (Even though this page is intended to focus on Japanese aviation history prior to 1945, postwar types are included here for the sake of completeness.)

| Date | Subject of Certification | Owner |

| Mar. 28, 2008 | First Production YS-11 (JA8610) and related materials |

National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo |

| Mar. 28, 2008 | Nakajima Type 91 Fighter | Saitama Prefecture |

| May 18, 2009 | Collection of Domestically Produced Civil Aircraft* |

Tokyo Metropolitan College of Industrial Technology |

| Dec. 19, 2010 | Propellers from Aircraft That Performed First Powered Flights in Japan |

National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo |

| Dec. 1, 2011 | Aichi Type 0 Reconnaissance Floatplane (E13A) |

City of Minami-Satsuma, Kagoshima Prefecture |

| Dec. 1, 2011 | Site of Yoyogi Training Ground** | Shibuya Ward, Tokyo |

| Mar. 27, 2014 | UF-XS Experimental Flying Boat (Grumman UF-1) |

JMSDF/Ministry of Defense |

| Mar. 27, 2014 | X1G1B High Lift Research Aircraft (Saab 91B) |

ALTA/Ministry of Defense |

| July 2, 2016 | Tachikawa Army Type 1 Twin- Engine Advanced Trainer (Ki-54) |

Aomori Prefecture Aviation Association |

| Added Mar. 25, 2023 |

Kawasaki Ki-61-IIKai Hien*** | Gifu-Kakamigahara Air and Space Museum |

* Civil aircraft dating from time of postwar resumption of aviation activities.

** From where the first powered flights in Japan were conducted in 1910.

*** See dedicated page on Gifu-Kakamigahara Air and Space Museum

For an aircraft to be considered for certification, the general criteria followed are whether the tests conducted or know-how and technologies that went into that specific aircraft’s design contributed in any way to the development of Japan’s aviation technologies. Seen as strengthening the likelihood of a type’s inclusion in terms of cultural value are that the aircraft is well preserved and as far as possible remains in the same condition it was when in experimental or operational use and thereby conveys something of the history of Japanese aircraft development.

The latest aircraft to be certified as an Aviation Heritage Asset is the Tachikawa Ki-54 recovered

The latest aircraft to be certified as an Aviation Heritage Asset is the Tachikawa Ki-54 recovered

from a lake in northern Japan. Taken by Shigezō Ōyanagi, director of the Misawa Aviation &

Science Museum where the wreck is housed, a photo of the salvage operation appeared on

the cover of the November 2016 issue of Puten News, the magazine of the Japan Aviation

Journalists’ Association, which contained Director Ōyanagi’s account of events.

It would thus appear that the odds-on favourite to be the next candidate to be granted Aviation Heritage Asset status, the Kawasaki Ki-61 (Type 3) Hien fighter currently on post-renovation display the Gifu-Kakamigahara Air and Space Museum, will be a shoo-in.

Of the two aircraft elevated in the peerage on the same day as the first recipients of Important Aviation Heritage Asset certification, one was the first production YS-11, which thus falls outside the scope of this website. Including the reasons for selection, the following roundup of the other award winners thus starts with an aircraft that represents a turning point in design production, from the period when the Japanese aviation industry was imitating overseas developments to one of self-reliance.

Nakajima Type 91 Fighter

Location: Tokorozawa Aviation Museum, Saitama Prefecture

In historical terms, this aircraft is extremely important for two reasons: as the sole survivor of the

In historical terms, this aircraft is extremely important for two reasons: as the sole survivor of the

around 450 Type 91s that were produced in two versions; and as an example of one of the few

Japanese-produced 1930s aircraft that remains in the same condition now as it was then.

First flown (in its initial Type NC form) in June 1928 and adopted by the IJAAF in 1931, the Type 91 Fighter was designed and developed by a Japanese team led by Yasushi Koyama (1900–1982) and Shigejirō Ohwada. Guidance was provided by two engineers from the French aircraft company Dewoitine, André Marie and Maxime Robin, whom the Nakajima Aircraft Research Institute (name changed to Nakajima Aircraft Company in 1931) had invited over in 1927.

As Nakajima had up until that time accumulated a wealth of experience only in the form of biplanes, a development adopting the new parasol-wing monoplane demanded by the Army was beset with difficulties and proved to be very time-consuming. However, by designing not only a prototype pattern aircraft but also making modifications and improvements that reflected the results of prototype flight testing, Japanese engineers—assisted by invaluable input from the French duo—learned a great deal about design and development methods that would provide the foundation for producing purely indigenous aircraft. On the basis of that knowledge, aircraft subsequently developed by Nakajima were to become the family of mainstay fighters operated by the IJAAF during World War II, as typified by the Ki-43 (Type 1) Hayabusa fighter. After the war, too, Nakajima aircraft engineers who had accumulated experience in the intervening period were also involved in the development of the YS-11, Japan’s first postwar, indigenously produced transport aircraft.

Capable of a maximum speed of more than 300 km/h, the Type 91 Fighter was the first to come close to emulating the standard set by the fighter aircraft produced in the United States and the other advanced aviation nations in Europe. A high-wing monoplane with a mixed wood and metal structure, the fighter featured a stressed-skin metal fuselage structure of aluminum alloy and a main wing comprising wooden parts and fabric covering on a thin, high-tensile steel framework.

After languishing for many years in the storage hangar at Tokorozawa, as seen here in October 2000,

After languishing for many years in the storage hangar at Tokorozawa, as seen here in October 2000,

the Type 91 was placed on permanent display in its current enclosed showcase within the Hangar

zone inside the main building in 2007. A diagram in the July 2006 issue of Aireview depicted

the aircraft, sporting replica wings, inside a frame flanked by showcases.

The Type 91 Fighter displayed at the Tokorozawa Aviation Museum was purchased by a resident of Miyagi Prefecture soon after the end of World War II, when the wing and engine were unfortunately already missing. In its current state, the aircraft comprises the fuselage, including the vertical stabilizer, and mainwheels, the surviving number and nameplates of which reveal the aircraft to be a Type 91 Model 2 with the construction number 237. The month and year of manufacture are given as January 1933, and acceptance checks and flight testing were carried out during the course of the following month. The lack of any fuselage hinomaru markings is understood to reflect the Revision to IJAAF Military Marking Provisions, which was circulated on February 1, 1937. The aircraft is thus believed to have still been flown operationally after that time.

In front of a certificate proclaiming the JAA’s Aviation Heritage Asset award stands a plaque

In front of a certificate proclaiming the JAA’s Aviation Heritage Asset award stands a plaque

(below) showing that the Type 91 also received recognition under the Ministry of Economy,

Trade and Industry’s Heritage of Industrial Modernization classification programme in 2008.

The process that culminated with the Type 91’s certification was set in train in August 2005, with the first of a series of meetings of a six-man aircraft preservation review committee. Seeking to come up with guidelines for the preservation of all aircraft of historical importance still extant in Japan, not just the Type 91, the committee included members from the fields of aeronautics and cultural property restoration as well as a representative from the JAA Aviation Heritage Inheritance Fund.

Positioning aircraft as cultural assets, the committee received a favourable response to the copy of the report submitted to Saitama Prefecture Governor Kiyoshi Ueda in January 2006. That the then Army airfield at Tokorozawa had been the location for the first flight of an indigenous aircraft, the Narahara No. 2 on May 5, 1911, would have added weight to the committee’s case.

From the available sources of information, such as the condition of the aircraft exterior and interior, the remaining paint as well as written records, the Type 91 is understood to still be in the condition of an aircraft that saw service before World War II. Factoring in what is known about this specific aircraft, a great deal of information has survived to the present day, such as the technical standards of the Japanese aviation industry in the 1930s—including the technologies and materials as well as construction methods needed to build the aircraft—and evidence concerning the people who built and flew this aircraft. As the aircraft was stored indoors for a long period of time, its state of preservation is good, with comparatively little onset of deterioration seen in its metal parts. There are places where corrosion has partially taken hold, but as the temperature and humidity of the display area as well as the condition of the aircraft are now being constantly monitored and recorded, the provisions are in place to bequeath this important aviation heritage asset long into the future.

Two photos to show intact, pristine Type 91s during the fighter’s heyday.

Two photos to show intact, pristine Type 91s during the fighter’s heyday.

(Above) A hot-rod Type 91 shares the flight line of what is most likely Hamamatsu airfield with more

sedate (left) Kawasaki Type 88-1 and (right) Mitsubishi Type 92 reconnaissance aircraft.

(Below) The kanji applied beneath the cockpit show that this early production example was funded

under the aikoku (patriotism) programme. Paid for by donations from the citizens of Hiroshima,

Shimane and Yamaguchi prefectures—and bearing the Shimane Prefecture city name Hamada

on its rear fuselage—the aircraft was dedicated at a ceremony held at an Army training

ground in Hiroshima on July 24, 1932.

(Photos via Wikimedia Commons; the full image of Aikoku 34 in all its glory can be found here [link].)

Propellers from Aircraft That Performed First Powered Flights in Japan

Location: National Museum of Nature and Science, Ueno Park, Tokyo

The propellers from the Henri Farman (foreground) and Hans Grade monoplane on display at the

The propellers from the Henri Farman (foreground) and Hans Grade monoplane on display at the

National Museum of Nature and Science in December 2013. Prone to wear and tear or damage, few

propellers exist from the pioneering days of Japanese aviation. There is, however, a distinct

possibility that these were among those used at the time of those first epoch-making flights

from Yoyogi Army Parade Ground in December 1910.

The first powered aircraft flights in Japan took place at the Yoyogi Army Parade Ground during the period December 11–20, 1910. Capt. Kumazo Hino successfully flew for the first time on December 14, piloting a 1910 Hans Grade monoplane imported from Germany. Capt. Yoshitoshi Tokugawa followed suit in his 1910 Henri Farman biplane, which had been imported from France, on December 19. The flights of both aircraft can and should be regarded as the starting point in Japanese aviation history. (For more details, please see the first feature article on this page.)

In the case of the Grade monoplane, the propeller used for that first flight was imported with the aircraft. In contrast, the propeller for the Farman’s first flight—a privately purchased propeller from a French-built Gnome engine—was sportingly provided by Navy engineer Sanji Narahara, as the propeller initially fitted had sustained damage during taxying. In the pioneering days of Japanese aviation, the majority of aircraft propellers were made of wood, but as the propellers of both the Grade and Farman aircraft at the time of the first flights featured metal blades and shafts, they were of a configuration that was little used in the early days other than on those two aircraft.

Both of the Museum’s propellers are metal. Although there are some differences in detail, both appear in photos thought to have been taken of the Grade and Farman at the time, after they had flown at the Yoyogi Army Parade Ground, and are essentially of the same shape and form. In the cases of both these aircraft, many propellers were purchased in Japan and from overseas, but these are thought to be the only examples in existence. A book published in 1944 (Kaigun Kōkūshibanashi [Tales of Naval Aviation History] by Vice Admiral Hideho Wada [1886–1972]) contains the statement: “Even now, the propellers of the aircraft used for the first flights of both captains are housed in the Science Museum in Ueno, where they retain their prestigious eternal form.” For these reasons, the staff at the Aviation Heritage Archive believe that the two propellers in the National Museum of Nature and Science are those that were fitted to the two aircraft.

It is thought that their current silver and black paint was not applied at that time. However, since neither major corrosion or damage nor evidence of tampering was found, it is also thought that the propellers remain in a condition close to that of the time when they were manufactured and in operational use.

Aichi Type 0 Reconnaissance Floatplane (E13A)

Location: Bansei Tokkō Peace Museum, Minami-Satsuma, Kagoshima Prefecture

An image taken from the leaflet of the Kaseda Peace Museum, the name by which today’s

An image taken from the leaflet of the Kaseda Peace Museum, the name by which today’s

Bansei Tokkō Peace Museum was known from its opening in May 1993 to late 2005,

when the city of Minami-Satsuma was formed by merging Kaseda City with other

towns in the area. Two clearer pictures can be found on the Minami-Satsuma

Municipal Tourism Association website [link].

As an island nation, Japan developed and operated a wide variety of seaplane types in the period up to the end of World War II. Formally adopted for service with the Imperial Japanese Naval Air Force (IJNAF) in 1940, the three-seat Type 0 Reconnaissance Seaplane was designed by the Aichi Watch and Electric Machinery Company, Ltd., which had boosted its development capabilities through technological collaboration with the famous Germany aircraft company, Ernst Heinkel Flugzeugwerke GmbH. Up until that time, Japan’s main reconnaissance seaplanes had comprised fabric-covered biplane designs, but as a low-wing, metal monoplane the Type 0 possessed a number of positive attributes, including excellent handling and stability as well as long range. Widely used by the IJNAF, a total of 1,423 were built, the highest production figure of any Japanese seaplane, and the type can thus be said to be a typical example of them, including in terms of its operational performance record.

An Aichi Type 0 Reconnaissance Floatplane receives some attention while resting on its beaching gear.

An Aichi Type 0 Reconnaissance Floatplane receives some attention while resting on its beaching gear.

The three-digit first part of the tail code, identifying the in this case unidentified ship to which the

aircraft was assigned, dates the photo as after August 1944. Prior to that date, alphanumeric tail

codes had been in use. (Photo from the November 1951 issue of The World’s Aircraft reproduced

with the kind permission of Hobun Shorin Co., Ltd.)

The Type 0 Reconnaissance Seaplane displayed at the Bansei Tokkō (Special Attack) Peace Museum had sunk to a depth of five meters, settling on the seabed around 600 meters from the shore at Kaseda (today Minami-Satsuma City) in Kagoshima Prefecture. The aircraft was salvaged by the Kaseda City authorities on August 22, 1992.

The inspection carried out after the salvage operation revealed the name of the aircraft’s manufacturer (Kyushu Aeroplane Company) and construction number (4116) inside the fuselage. The number of the unit to which the aircraft had been assigned (302nd Reconnaissance Squadron) was found on equipment that remained inside the aircraft. Using these and other snippets of information, the names of the crew members were discovered, and from the evidence and eyewitness accounts provided it was confirmed that the aircraft had headed for Okinawa on a night reconnaissance mission on June 4, 1945, but run out of fuel upon its return. The pilot had made a forced landing off Fukiagehama; he and the other two crew members escaped unhurt, but the aircraft subsequently sank.

Apart from the propeller and part of the cockpit that remained exposed above the seabed, the aircraft was entirely embedded in sand. Despite having been submerged for such a long period of time, the corrosion and damage to the aircraft were comparatively light, but there was no sign of the floats. In addition, only part of the wooden tail remained.

Two more photos to show intact Type 0 (E13A) floatplanes in typical settings during the type’s heyday.

Two more photos to show intact Type 0 (E13A) floatplanes in typical settings during the type’s heyday.

(Above) A Type 0 three-seat reconnaissance seaplane hurtles down the port-side Type 2, Model 5

catapult of the heavy cruiser Ashigara, somewhere in the Java Sea in May 1943.

(Below) Two E13A1s from the 958th Kōkūtai photographed on a beach circa 1943. The unit

operated in the Rabaul area of New Britain, which is now part of Papua New Guinea)

(PNG), with forward bases at Shortland in Bougainville (also now in PNG) and

Rekata Bay in the Solomon Islands. (Photos via Wikimedia Commons)

In light of the aircraft’s condition following its recovery, the Kaseda City authorities decided to reproduce the conditions the aircraft was in on the seabed prior to the salvage operation rather than to newly fabricate any missing parts, including the floats. Thus the work of the unit members from the aviation engineering workshop at Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) Kanoya air base, who were responsible for such aspects as preservation treatment, focused on the removal of rust, clogged sand and oyster shells as well as on rust protection. No repairs or repainting to simply improve the external appearance were carried out. For this reason, even now verification can be made of the aircraft’s state when in operational service, including of the wooden spars on the tail and of the red paint of the hinomaru national markings that remain on the wings. The state of the aircraft is not necessarily that good, but having been preserved along with the many items of equipment that had remained in the cockpit, great value is derived from the ability to gain an insight into the aircraft’s appearance when in operational service. It is rare for a Japanese aircraft from the war period to still contain a lot of equipment, to the extent that even the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in the United States uses the Type 0 as a reference when restoring the Japanese aircraft in its possession.

During World War II, Japan led the world in the development and operation of a large number of seaplanes. The aircraft owned by Minami-Satsuma City is one of only two surviving Type 0 reconnaissance seaplanes in Japan—the other is displayed in a dilapidated state outside the PR building at JASDF Gifu AB (link)—and to a great extent remains in the state it was when in operational service. Showcasing the aircraft’s history to this day, the display was also awarded high marks for its way of putting a stored cultural asset to practical use. For these reasons, the Type 0 Reconnaissance Seaplane in Minami-Satsuma has been recognized as an important artefact that presents the history of IJNAF seaplanes to this day and can be said to be of very high cultural value.

Site of Yoyogi Training Ground

Yoyogi Park and the Meiji Shrine, as seen from Tokyo’s Park Hyatt Hotel in April 2015.

Yoyogi Park and the Meiji Shrine, as seen from Tokyo’s Park Hyatt Hotel in April 2015.

(Photo: Jc8136 via Wikimedia Commons)

An event that should be regarded as the starting point of the country’s aviation history, the first powered aircraft flights in Japan were planned by the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group that had been organized by the Imperial Japanese Army to advance research into flying machines.

The Army Ministry had just established the Yoyogi Army Parade Ground in 1909, the year prior to those first flights, as a location for troop training on the hilly area that straddled the town of Shibuya and the village of Yoyohata in Tokyo. The zone defined as having been at that time the designated flying area of the Provisional Military Balloon Study Group is situated in what is today Tokyo’s Shibuya Ward. As roads pass along the eastern, western and southern boundary lines of that flying area in almost the same positions, the Aviation Heritage Archive team was able to confirm those boundaries and the area, which today includes several famous landmarks. Encompassing Meiji Shrine and Yoyogi Park, the area to the north even today retains the topography gleaned from a contemporary relief map and reveals traces of its appearance at the time of those first flights. Among the historical sites related to Japanese aviation, this area can be said to be extremely valuable for these reasons. (For more details of the events themselves, please see the first feature article on this page.)

UF-XS Experimental Flying Boat

Location: Gifu-Kakamigahara Air and Space Museum, Gifu Prefecture

The UF-XS aloft on a test flight. The standard, four-man crew comprised a pilot and co-pilot,

The UF-XS aloft on a test flight. The standard, four-man crew comprised a pilot and co-pilot,

a flight engineer and an engineer tasked with monitoring any on-board test equipment.

(Photo: ShinMaywa Industries, Ltd.)

To conduct tests using an experimental aircraft in the development of what was to become the indigenously produced, four-engined PS-1 anti-submarine patrol aircraft, the then Japan Defense Agency received the offer from the United States of a Grumman UF-1 Albatross amphibian (BuNo. 149822) and produced the UF-XS experimental amphibian in 1960. Although the Japanese had accumulated advanced flying boat technologies both before and during the Pacific War, the aim was to correct a major shortcoming by improving takeoff and landing performance in rough sea conditions. Fittingly, the UF-XS design team was headed by Shizuo Kikuhara (1906–91), who had been the chief designer of the wartime Type 2 Flying Boat.

To adapt the UF-1 for its role as an experimental flying boat, the main areas of modification thus involved the following:

- A newly designed boat hull, based on a unique concept that included wave suppression devices, to enable the aircraft to take off from and land on the ocean in wave heights of the order of three meters.

- The provision of a system to blow high-pressure air from two turboshaft engines added within the hull over the main wing flaps, ailerons, elevators and rudder to improve short takeoff and landing (STOL) performance as well as handling at low speeds.

- The provision of automatic stabilization equipment to ensure stability and facilitate control at low speeds.

- Changing the aircraft from a twin- to a four-engined configuration.

The UF-XS at rest on its beaching gear. The removal of the UF-1’s landing gear, which also helped

The UF-XS at rest on its beaching gear. The removal of the UF-1’s landing gear, which also helped

to save weight, also served to familiarize its flight and support personnel with

flying boat handling procedures. (Photo: JMSDF Kanoya)

Taking to the skies for the first time at noon on December 25, 1962 (link), the UF-XS carried the tailcode オ(‘O’)-9911, the ‘O’ being the tail code of the JMSDF’s Omura Fleet Air Squadron. The aircraft continued to be utilized in a range of flight tests until 1964. The results obtained and conclusions derived from those tests were incorporated into the design of the PS-1 flying boat, the first aircraft of its kind to be built in Japan after the war, and have been handed down to the current US-2 amphibian.

At the conclusion of its test program, the UF-XS was moved to JMSDF Shimofusa air base in Chiba Prefecture, withdrawn from use in June 1967 and placed in storage there. In 1975, the aircraft was loaned to the Tokai University Aerospace Museum within the Miho Bunka Land amusement park in the Shimizu district of Shizuoka City, Shizuoka Prefecture, where it was kept out in the open (as shown in this series of photos from August 1980 [link]) until acquired for display at the then Kakamigahara Aerospace Museum (now Gifu-Kakamigahara Air and Space Museum) in 1993. At the time the aircraft was brought to the museum, it was missing the two turboshaft engines that had been added to provide the high-pressure air and parts such as ducts. Due to the aircraft having been displayed outside, there were also places where metal corrosion had made inroads. Furthermore, as modifications had been carried out to install an opening and a steel passageway that had enabled visitors to enter the aircraft’s interior, the aircraft had ended up being significantly different to what it had looked like at the time when it was used as a flying testbed. For that reason, repair and restoration work based on the manufacturing plans of the time was carried out by ShinMaywa Industries, Ltd., the company (then known as Shin Meiwa Industry Co., Ltd.) that had originally modified the aircraft. When reproducing parts that had been lost, measures were taken to distinguish between original and other parts, for example by applying identification stamps to tell them apart.

As only one aircraft was produced for the purpose of PS-1 development, the UF-XS is a unique aircraft that represents the starting point of Japan’s postwar flying boat development that has continued to the US-2 amphibian. Having carried out the appropriate repair and restoration work to return the aircraft to the original condition of its flying testbed days, the UF-XS now has value as a cultural asset.

For these reasons, the Aviation Heritage Archive team members deemed that the UF-XS Experimental Flying Boat, owned by the Ministry of Defense/JMSDF and stored and displayed at the Gifu-Kakamigahara Air and Space Museum, can be regarded as an important aviation heritage asset that conveys the history of Japan’s flying boat development.

Modified beyond all recognition from the standard UF-1 Albatross on which it was based, the UF-XS

Modified beyond all recognition from the standard UF-1 Albatross on which it was based, the UF-XS

cuts an imposing figure in the main exhibition hall of the then Kakamigahara Aerospace

Science Museum in October 2000.

The bulbous fairing above the cockpit housed two 1,050 hp General Electric T58-GE-6 engines for the

The bulbous fairing above the cockpit housed two 1,050 hp General Electric T58-GE-6 engines for the

boundary layer control system. This meant that, particularly when in STOL configuration,

the crew had to endure deafening noise levels.

UF-XS Off-Site Photo Gallery

The UF-XS at rest on the slipway at the Shin Meiwa (now ShinMaywa) Konan Plant in Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture, circa January 1963 (link).

During preparations for a test flight from the Konan Plant, the inboard 1,425 hp Wright Cyclone R-1820 engines, retained from the UF-1 and powering three-bladed propellers, are run up to their operating temperature. Added as part of the modifications, the outer 600 hp Wright Cyclone R-1340 engines drove twin-bladed props (link). Although the UF-XS, like the UF-1, was capable of being fitted with jet-assisted takeoff bottles, these were never fitted.

At the end of 1964, the UF-XS was used in the taxy trials of the wave suppression system (referred to in Japanese as a ‘hydro damper’), by which special grooves were attached along the bottom of the forward section of the hull. Water splashing upward was allowed to escape in a downward direction (link).

X1G1B High Lift Research Aircraft (Saab 91)

Location: Gifu-Kakamigahara Air and Space Museum, Gifu Prefecture

At one stage fitted with an internal gas turbine and sporting a large exhaust in its rear fuselage, the

At one stage fitted with an internal gas turbine and sporting a large exhaust in its rear fuselage, the

series of modifications made to this Saab 91, originally imported into Japan in 1953, represented a

quantum leap in Japanese research into the realm of high-lift devices. Having fallen behind

technologically during the seven-year postwar ban on aviation activities, this aircraft

played a critical role in Japan’s attempts to make up for lost time.

(Photo: Hunini via Wikimedia Commons)

The Saab 91 Safir that provided the basis of the X1G1B high-lift research aircraft was a well-known type of training/liaison aircraft that had first flown in 1945. A total of 323 were produced in Sweden and the Netherlands and exported to a number of countries. Differing in terms of engine and equipment fit, the sub-types ranged from the Saab 91A to the 91D.

In May 1953, the then National Safety Agency imported as a candidate primary training aircraft a Saab 91B (c/n 91-201) that had already seen military service as the first Royal Swedish Air Force Sk50b from July to November 1952. Registered to Asahi Airlines Co. as JA3055, the aircraft was based at Fujisawa airfield, Kanagawa Prefecture.

Seen here at an unnamed, rain-soaked location, the then newly imported Saab 91B made its debut

Seen here at an unnamed, rain-soaked location, the then newly imported Saab 91B made its debut

public flight from Tokyo Airfield on May 30, 1953, just over a month after the facility

(now Tokyo Heliport) had opened for business on reclaimed land.

(Photo from the August 1953 issue of The World’s Aircraft reproduced with the

kind permission of Hobun Shorin Co., Ltd.)

In March 1956, the Beech T-34A Mentor having long since been adopted as the JASDF trainer, the aircraft was purchased for 6.8 million yen by the Technical Research & Development Institute (TRDI, since 2015 the Acquisition, Technology and Logistics Agency) of the then Japan Defense Agency (today the Ministry of Defense) and gained a new lease of life in the testing of high-lift devices. At that time, the aircraft’s previous registration (JA3055) was cancelled and the TRDI provided with the serial TX-7101 in April 1956.

Facilitated by the lack of fuel tanks in the wings, the aircraft took on a number of different guises. Given the basic designation X1G—standing for experimental first aircraft Giken (the abbreviation for TRDI)—as the X1G1 the aircraft was fitted with a newly designed, Japanese-built main wing that featured full-span flaps and spoilers. In the cockpit, it was presumably at this time that a flap position indicator was added on a central pedestal. Work to confirm the wing’s effectiveness, including flight testing, commenced in December 1957 and ended in August the following year.

From April 1959 to September 1960, the now X1G2 was fitted with a 260 hp Continental engine in place of the original 190 hp Lycoming to cope with the extra weight from having a gas turbine installed, complete with a large exhaust, in its fuselage (link). The gas turbine formed part of an experimental boundary layer control system designed to increase lift by blowing high-pressure air over the upper surfaces of the wings and flaps via devices fitted to the leading and trailing edge of the main wings. Formerly of fabric, the skins of the rudder and elevators were changed to metal. During 1960, the aircraft was flown from Chofu airfield in Tokyo.

As the X1G3 from April to August 1962, attempts were made to solve the problem of high-lift device controllability by suppressing wingtip vortices. The distinctive feature of this modification was the addition of rectangular end plates to the wings.

In late 1962, its career in research having come to an end, the now four-seater aircraft was used for liaison purposes, again fitted with the X1G1 main wing but designated X1G1B as the Continental engine was retained. Following its withdrawal from service in 1986, the aircraft was stored within the TRDI’s Gifu test area. The aircraft has been on indoor display at Kakamigahara since the then aerospace museum (now Gifu-Kakamigahara Air and Space Museum) opened its doors in 1996.

Taken at the same time as the lead photo, this view shows the modifications made to the

Taken at the same time as the lead photo, this view shows the modifications made to the

horizontal tailplane. The Japanese on the rear fuselage reads Technical Research &

Development Institute, Gifu Test Center. (Photo: Hunini via Wikimedia Commons)

As the know-how and technologies gained from the tests carried out on this aircraft were utilized in designing the C-1 transport, the PS-1 flying boat and the MU-2 business aircraft, its contribution to the development of Japan’s aviation technologies was enormous. The technology by which high-pressure air is blown over the upper surfaces of the flaps in particular has been continued, via the UF-XS experimental amphibian, through to the latest US-2 amphibian. Other than maintenance needed on parts of its external paintwork that had deteriorated over time, the aircraft needed no work carried out at the time of its addition to the museum collection. Well preserved in the condition it was when in operational use, including traces of its time as a research aircraft, its cultural value remains high.

Tachikawa Army Type 1 Twin-Engine Advanced Trainer (Ki-54)

Location (since Nov. 2020): Tachihi Holdings, Building 5, Takamatsu-cho, Tachikawa, Tokyo (formerly at Misawa Aviation & Science Museum, Aomori Prefecture)

A composite photo shows the salvaged Type 1 Twin-Engine Advanced Trainer on display at the

A composite photo shows the salvaged Type 1 Twin-Engine Advanced Trainer on display at the

Misawa Aviation & Science Museum in May 2014. Of the 1,342 of this type of aircraft that were

built only three remain, the other examples being in Australia and China.

(Photo: ‘Aomorikuma’ via Wikimedia Commons)

On September 27, 1943, a lone Tachikawa Ki-54 (Hickory) trainer of the 38th Flying Regiment took off from Shinonome airfield in Noshiro, Akita Prefecture, and headed across to Takadate airfield in Hachinohe, Aomori Prefecture. The aircraft was carrying spare parts for an unserviceable Ki-46 (Dinah) reconnaissance aircraft, the principal type on which the unit had formed in April of that year. Having itself reportedly suffered the failure of its port engine en route, the Ki-54 came down in Lake Towada, which straddles the border between the two prefectures. Only one of the four crew members was lucky enough to survive. The January 2017 issue of the twice yearly JAA publication Air Forum/Kōkū to Bunka (Aviation and Culture) states that the exact cause of the crash remains unknown to this day.

Fast forward to September 1, 2012, and the fuselage of that aircraft, which had been located at a depth of 190 feet (57 metres) on August 7, 2010, saw the light of day for the first time in 69 years (link). An engine was salvaged the following day, and the maker’s name Bridgestone was still discernable on a tyre that was brought to the surface four days later.

As a wartime incident, details of the incident remained classified, but Lake Towada was listed as the site of a war grave in Shonen Hikōheishi (Air Cadet History) published in 1983 by the Air Cadet Association.

Misawa Aviation & Science Museum (MA&SM) Director Shigezō Ōyanagi contributed a detailed two-part account of the discovery and salvage operations in the January and February 2013 issues of Kōkū Fan, but the following account and key dates then and since listed below are summarized from his report in the November 2016 issue of Puten News, the magazine of the Japan Aviation Journalists’ Association (JAJA).

(Above and below) Two views of the Ki-54, one of its nine-cylinder Hitachi Ha-9a radial engines and

(Above and below) Two views of the Ki-54, one of its nine-cylinder Hitachi Ha-9a radial engines and

other recovered artefacts, taken on the day of the aircraft’s official certification as an

aviation heritage asset, July 2, 2016.

(Photos: Yukio Suzuki, Executive Director, Japan Aviation Journalists’ Association)

Ōyanagi first became aware of the aircraft’s existence when he came across an article entitled The Army Aircraft Asleep in Lake Towada, which appeared in The Daily Yomiuri newspaper of March 9, 1995, before he went on to write Aomoriken Kōkūshi (The History of Aviation in Aomori Prefecture), which was published in 1998.

In 2008, five years after the MA&SM’s August 2003 opening, a project was finally started to try and pinpoint the likely crash location by first collecting any eyewitness information and then conducting a search with an underwater camera. The efforts bore fruit on that day in August 2010, when the aircraft was finally discovered. The first salvage operation, started on March 20, 2011, was stopped after two days because the wreck was embedded in clay on the seabed and impossible to move.

A second attempt was made from August 24, 2012, but things did not work out with a lift four days later, and only a pitot tube could be brought to the surface. New equipment utilized in support of the divers’ efforts on August 30 was a robot camera, which quickly paid dividends. A visit to a local shrine on September 3 to pay respects to the souls of the crew members who had lost their lives was followed by a press briefing at MA&SM on September 6.

The fuselage and other major assemblies were transported to Aomori marina, where they were cleaned on September 7, 2012. Arranged on display at the MA&SM the following day, the number of visitors had surpassed the 100,000 mark on December 4 that year. That same day a donation was received from real estate company Tachihi Holdings Co., Ltd., the modern-day successor to Tachikawa Aircraft and since November 2020 the aircraft’s fitting custodian.

A still from a nine-minute YouTube video, credited to Masao (?) Hikoyama (link), the first three

A still from a nine-minute YouTube video, credited to Masao (?) Hikoyama (link), the first three

minutes or so of which tell the story of the Lake Towada Ki-54 from discovery to salvage.

Selected Captions/Information from above YouTube Video

0:09 (Main title) Lake Towada: 67th Year Requiem

0:11 On the Bottom of Lake Towada

0:26 Engine / 0:32 Cockpit

1:02 Shunji Kanemura (reading of name to be confirmed, aged 81 at time of interview) describes aircraft engine sounds as having been abnormal and how his father helped to rescue the sole survivor.

1:24 July 12, 2010 Start of Lake Towada Survey

1:37 Aug. 4, 2010 Variety of Aircraft Forms Captured (with acoustic depth finder)

1:59 CG topography of lake bed in area known as Nakanoumi (max. depth of 325 metres)

2:14 Aug. 8, 2010 Filming of Sunken Aircraft on Lakebed

2:47 September 2012 (Images of aircraft salvage)

(3:35 to 5:25) Media briefing with (centre) MA&SM Director Shigezō Ōyanagi flanked by senior management representatives from (left) the construction company that provided the lifting equipment and the president of the marine survey company, Windy Network Corporation.

(5:26 to 8:40) Nov. 10, 2012 Opening ceremony of Ki-54 exhibit at MA&SM (speeches/ribbon-cutting ceremony)

8:41 to end Video of aircraft, including interior